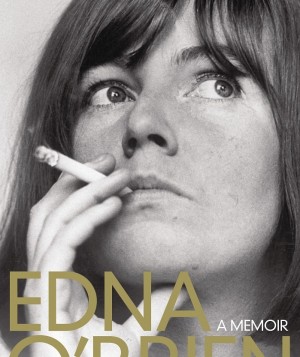

Looking through a “Gloss” Darkly: Edna O’Brien Walks a Long Blue Road in Black Suede Shoes

“That is the mystery about writing: it comes out of afflictions, out of the gouged times, when the heart is cut open,” reflects Edna O’Brien in her much-anticipated new memoir, Country Girl. Since her 1960 debut onto the literary scene with her controversial novel, The Country Girls, the world has waited for the Irish ex-pat to tell all. And while her prose glistens like spring dew on St. Stephen’s Green, its refreshing tone is that of a bashful youth.

O’Brien tells us from the onset that this is a book she “swore [she] would never write.” And on occasion she even seems irritated with the task at hand. But time ages even the gilded among us, and for O’Brien, at 82, it was a piano that prompted her to stir up old memories and scribe them into a lavish gesture to life’s “bounties.” It’s not, mind you, the piano we see her move from house to house — symbolic of the untethered, wayward Irish daughter’s heavy, somber timbre — but the one that brings joy from hearing the “drones of bees and wasps” or contentedness from listening to Paul McCartney sing her son a lullaby. On the first page, the reader learns a nurse has informed O’Brien that her hearing has gone like a “broken piano.” And with that she sets out to retune her life memories.

On the surface, it’s a straightforward chronicle, detailing fond moments, painful heartbreaks and gratifying jaunts with some of the greatest talents of the 20th century. There is Samuel Beckett, R. D. Laing, Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, Marianne Faithfull, Sean Connery, Jane Fonda, Shirley MacLaine and Jude Law. And then there’s Jackie Onassis — one of O’Brien’s closest friends — Prime Minister Harold Wilson and Hillary Clinton. It’s a whirlwind of cultural and political icons that O’Brien often entertains in London and New York with the skilled hands of a professional chef.

Broken into four parts, we follow her as she grows up in a claustrophobic Irish village, attends an austere convent, moves to “enthralling” Dublin, marries (and divorces) a boorish, manipulative older man, negotiates public acclaim and scorn over her frank novels on Catholicism and women’s sexuality, embraces, at times awkwardly, her newfound celebrity and adjusts to a solitary life in her later years. Dates, locations and names are all there. But there’s also something inherently missing. Her memoir could be likened to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, where, like Estragon and Vladimir, the reader keeps waiting for the title character to emerge.

Upon closer examination, however, O’Brien isn’t the main character of her tale, for she is, in many ways, still searching for her own Godot — an elusive, metaphysical construct, neither explainable nor attainable, and all the more anticipated as one matures. As was the case throughout her life, the Celtic island submerges and resurfaces in Country Girl as a larger than life juggernaut of contradictions, pain, fury, charm and curiosity. “It is impossible to capture the essence of love in writing,” she reflects at one point, “only its symptoms remain, the erotic absorption, the huge disparity between the times together and the times apart, the sense of being excluded.” The memoir, an artistic act of love, is, at its heart, an elegiac journey in which O’Brien, embarking on her fifth act, seeks to come to terms with her greatest and most painful lover of all: enigmatic Ireland.

Oh, Ireland! The land that spat upon her writers through censorship and book burnings, including James Joyce, Beckett, Seán Ó Faoláin, Frank O’Connor and O’Brien herself. The land operating under such archaic social mores that O’Brien compares 1950s Dublin to 1500s Salamanca. And until a 2007 peace accord, it was the land divided by an imaginary fault line that will forever bind Catholics and Protestants, republicans and loyalists together as thousands of ghosts haunt the streets of Dublin and Belfast and many a village in between — an eternal, muffled reminder of countless innocent lives taken, in the name of God, through bloody violence.

In a conversation with long-time friend, Beckett, O’Brien describes her final resting place “on an island in the Shannon, so isolated, with its several churches, roofs opened to the skies, wild birds swooping in and out, tombstones chalked with lichen.” Beckett, himself in exile, is struck by the notion that she would return to the land that refused to accept Joyce’s ashes for proper burial. It is here that O’Brien subtly reveals herself by explaining away Beckett’s contempt for his motherland, “I knew he could not have written of the ditches and the daisies and the ruin strewn land unless he had loved it with such a beautiful, sad, and imperishable loneliness.”

Ireland’s rugged landscape nurtured O’Brien’s soul and talent as a child. She found comfort and creative inspiration in the fields just beyond her family’s home — an Arcadian sanctuary away from her drunken father and stolid mother. The town, with its “twenty-seven public houses, three grocery shops, one drapery, one chemist, no cinema, and no library” suffocated her from an early age. For a time she would find room to breathe in Dublin, but ultimately found personal freedom in London, where she’s lived for five decades. And while she knew she would always return to her home, she also knew that she “would never come back entirely.”

(Article continued on next page)