Chaos to Couture to Confusion: Punk Comes To the Met

A life-size replica of the famed Manhattan nightclub CBGB bathroom, initiates an immersive effort to transport us back to the antipathetic aesthetic circa. 1975. The Ramones bang and strum on loudspeakers, while shaky performance film footage of Sid Vicious and other rockers — edited by fashion photographer and filmmaker Nick Knight — flash on giant projection screens to punctuate themes of grit, grime and youthful indiscretions. The ambient soundtracks and visual looping create the kind of disorienting atmosphere that perhaps the pioneering figures of punk often felt themselves, but the time warp is short-lived.

Walking into the new Punk: Chaos to Couture exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, you’ll be struck by an abrupt occasion for a historical survey. Narrowing in on prim runway looks donning apparent punk trappings, the Met lays out points of reference to elucidate how niche street outfitting transitioned into made-to-wear custom fittings. In a word, this show lacks context. It’s not made entirely clear to what exactly punk was reacting, and it overlooks an opportunity to engage in its relevancy through drawing a parallel to the current cultural DIY predilection. The punk era’s influence on high fashion certainly can merit review, but distilling an anti-establishment youth movement at an institution like the Met is bound to be amiss. Archival underpinnings are glaringly omitted from the museum’s second-floor Cantor galleries, resulting in a sloppy concision that betrays the haste of an alleged timeline.

While the chaos is dated back to the mid-‘70s — ignoring the philosophical and artistic influence of its precursors, namely, Situationism and Dadaism — the majority of the approximately 100 pieces of couture on display can be found in fashion catalogues from within the past 10 years, and consequently, negates the coherence of its retrospective. More specifically, a sample pool of Rodarte’s fall 2008 knit dress; a notorious Versace evening dress with oversized safety pins from the spring/summer collection of 1994; a chain-draped Balenciaga mini-dress from autumn/winter of 2004; a pink silk chiffon Givenchy dress with gold zips from spring/summer 2011; Gareth Pugh voluminous topiary-looking garbage bag gowns from 2006; and a 2007 Dolce & Gabbana black tulle and lace gown, cinched with a half-foot-wide silver metal plated belt complete with padlock and key, coalesce to constitute the exhibit’s thesis. But stitching together a historical narrative from clothing seen on runway shows as recent as Vivienne Westwood’s autumn/winter 2013-2014 fosters an intellectually premature, anecdotally, underdeveloped, and overall, superficial reception.

Pinning together the show’s disjointed parts is the so-called “do-it-yourself ethos” that defines punk modality, and repetitiously appears throughout the accompanying wall text with such frequency as to invoke juvenile insistence, rather than institutional authority. Instead of holistically evoking punk, the show imposes abstractions through four thematic “expressions” of this ethos: Hardware, Bricolage, Graffiti and Agitprop and Destroy. Exhibitionist hairstylist Guido Palau’s multi-colored, mop head wigs — devoid of any actually styling — further reflect the exhibit’s basic treatment of its subject. A stylistic progression from studs, spikes, chains, zippers, padlocks, safety pins and razor blades to the use of recycled materials from trash and consumer culture, onto provocation and confrontation through images and text, concludes with torn and shredded looks associated with deconstructionism.

Dividing the narrative of punk into four distinctive parts is an effective organizational tactic that parses its visual language. The first gallery’s black rubber lined walls — subtly paying homage to the interior of punk fashion’s original purveyor Malcolm McLaren’s SEX boutique (later renamed Seditionaries) — anchor vintage Westwood garments alongside more recent iterations from Yohji Yamamoto, Junya Watanabe, and Christopher Bailey for Burberry. The all-white second gallery mostly features black or white evening gowns mounted on elevated pedestals in rounded classical niches to impart juxtaposition between high and low cultural aesthetics. Zandra Rhodes, one of the first designers to borrow from the punks, is represented by two slinky 1977 evening gowns consisting of cutouts, beaded safety pins and metal-ball chains. Reinventing the reuse and recycling of Bricolage, i.e. discards, Belgian fashion star Maison Martin Margiela fulfills the look to the utmost degree with jackets and vests made from a combination of broken plates, Paris Métro posters, strands of imitation pearls and multi-colored strips of newsprint covered with clear tape. It is here that the eclecticism of punk styling is shown to its full effect.

The shiny black painted backdrop of the third room offsets the bright colors, bold graphics and patterns of Stephen Sprouse dresses and Dolce & Gabbana ball gowns to be heard loud and clear. The hand-drawn illustrations and explicit text feel the most authentic to the rough-and-ready roots of punk. The tour concludes with COMME des GARÇONS, Calvin Klein and Chanel wool felt and mohair looks, thinly threaded to expose as much skin as possible, along with all-too-familiar ripped denim and cotton tanks. The illuminated words “No Future” from the lyrics of “God Save the Queen” by the Sex Pistols, hang against the two black walls opposite each other. The spectrum of the exhibit is vast, relying on an impressive multiplicity of tacit source materials. By the end of it, when you’re confronted by a hot pint wigged mannequin donning a frontless Margiela “gown” and upturned middle-finger — apt in considering how the exhibit manages to glorify the bastardization of punk in place of illustrating its aesthetic impact — you’re left wondering how did this happen?

Andrew Bolton began undertaking his vision last June, as the Met curator who conceived and organized the exhibition. Originally from England, Bolton had been working for three years as a contemporary fashion research assistant in London’s Victoria and Albert — the world’s largest museum of decorative art and design — before he was offered an associate curator position in 2002 from the Met’s Costume Institute’s long-standing curator-in-charge, Harold Koda. In a recent New Yorker profile, Bolton credits Koda and Richard Martin, a former curator-in-charge, with shaping his personal approach to fashion, “who used the present to enliven the past, and the past to inform the present.” This sensibility was the principle guide in Bolton’s previous two shows: Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty” (2011), which is one of the Met’s most highly attended exhibitions to date, and last year’s Schiaparelli and Prada: Impossible Conversations, which compared Italian designers from past and present periods. Both were lauded as major successes and cemented Bolton’s credibility as a scholarly visionary, responsible for revitalizing the Costume Institute’s status.

The transatlantic phenomenon of punk proves to be his most challenging project to date, and, as Koda admitted to The New Yorker in reference to when Bolton first started at the Met, perhaps not entirely surprising either, “What I think he didn’t understand at first is that we have a different audience from the one he had in Europe. There, people stand around reading labels; here, if there’s someone in the way, they move on. Andrew had to get used to this.” It would seem that in the case of punk, favoring brevity over depth, the scope exceeds the necessity of compromise impressed upon Bolton’s ambitions. The medium itself doesn’t satisfy the message of everything punk has to say, or perhaps the layers of punk are too numerous to be simply conveyed through layers of fabric.

Bolton’s culpability is only attributable insofar that we consider that the main funding for the Costume Institute exhibitions has always come from the fashion industry. Punk: Chaos to Couture was made possible by Moda Operandi, a three-year-old retail fashion outlet that describes itself as “the world’s premier online luxury retailer.” The Met’s marketing department presented a preliminary mockup of the show to get Moda to sign on. As evidenced by the commercial fashion that predominates the exhibit, the corporate sponsorship’s threads of influence run deep and thick in dressing up subtle marketing as sartorial assessment. The show’s parade of mannequins advertises the idea of haute couture as a viable expression of individuality in keeping with Bolton’s own philosophy, “haute couture is an ideal, but fashion itself is democratic. We all wear it,” but form fails to follow function, as its presentation avoids the praxis of punk, i.e. articulating the personal is political paradigm through manners of dress. Aside from a coincidence of copy between an “ethos of discovery” on Moda’s Web site and the “ethos of do-it-yourself” that dictates Punk: Chaos to Couture, Moda released a new exclusive punk collection in conjunction with the museum show it funded. In business marketing jargon this is known as cross-promotion, and frankly, it’s offensive. The most regrettable aspect of this exhibition is not in the shortcomings of its execution. It’s that the Met allowed itself to be transformed from an institution of learning into an auxiliary vehicle for product sales.

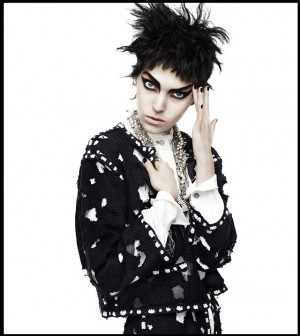

Featured image: Karl Lagerfeld (French, born Hamburg, 1938) for House of Chanel (French, founded 1913). Vogue, March 2011. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Photograph by David Sims.