Artist of the Week 2/13-2/19: Lalage Snow Gives a Voice to the Faces Behind the War

GALO: The soldiers’ faces in We Are The Not Dead tend to appear sullen, brooding, and wistful, reflecting the trauma inherent to combat. Did you give them any direction when taking their photograph?

LS: It depended on the individual. Most of the guys were totally natural and able to talk to me while I photographed. One or two found it awkward having a camera so close. (I shot everything on 50mm, which meant I was physically invasive — a deliberate ploy.) I’d let them answer my questions (which were pretty endless and probing), and got to know their facial expressions when thinking or talking about something. So when it came to photographing them, I could direct them ever so slightly, but not dramatically — usually, it was just, “keep very still” or “shift a little forward please” or “look directly at me.” But most of the time, when they asked me, “Where do you want me to look?” I’d say, “Wherever you’d like to look.”

GALO: The amount of contrast, light, and image clarity seems to vary over time in each of the photographs, were you deliberately imparting a particular aesthetic to your images for the series?

LS: Some people have been hypercritical about the lighting. Little do they know that I’m a lighting dunce and 100 percent ignoramus when it comes to using flash or fixed studio lights, or even those bendy reflector things. I struggled with lighting, and it shows; the before and after shots were taken in a storeroom in the barracks in Scotland in spring and autumn. Edinburgh light is changeable at the best of times — add some very changeable weather and it’s a recipe for one very confused photographer. The room was lit by two skylights and I used a black sheet as the backdrop. Using a 50mm lens, I was physically about half a meter from the subject, which is incredibly invasive. The “during” shots were in light that was totally different — Afghanistan, the desert, the middle of summer; it was almost impossible to control, and I often didn’t have a choice of time of day and had to work very quickly. My black sheet flew away when a helicopter landed, so I had to tape bin bags together, which was less than ideal as even black bin bags reflect light. I wanted to keep the three images as even as possible so that you, as a viewer, concentrate on the faces and the personal testimonies. If I were to do it again, I’d go on a lighting course, or at least learn how to use one of those reflector things.

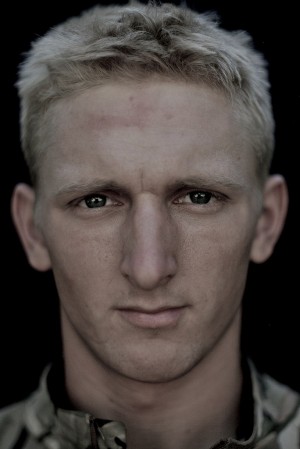

Corporal Steven Gibson, 29, Mussleburgh. Photo and testimony courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

First image: “I am afraid of not coming back. My daughter is due on the 8th of August and so I am worried for my missus. I am going to miss her and the kids.” Second image: “A lot of the guys have bibles with them — they know it’s a split second from going from bad to worse. I have read up to page 27. I have never read the bible before. This place opens your eyes up. You hear op minimize come one and it brings it all home. You know that somewhere a soldier has been badly injured or worse, so reading the bible is like trying to make peace with someone. I keep rosary beads in my pocket and a ring that my father had on a chain. He passed away just before I came out.”

GALO: How was the durational separation between the three photographs of a given soldier determined and did you have a preconceived criteria for who you photographed?

LS: It ended up being about three months: March, June and October. The “during” shots were at the whim of the MOD. I only found out I had been “approved” to go out to Helmand about a week before going. It was six months of paperwork and uncertainty. The MOD is pretty bureaucratic to work through; they only allow a set number of journalists in there at any time and as a lowly freelance photographer, you are bottom of the pile. Unlike the Americans, they give you set dates, which are impossible to change or extend. Prior to deployment, the Commanding Officer of 1 Scots attached me to A Company (out of A, B, C and D company — in the army, a battalion is made up of five companies or so. A company is three platoons; a platoon is about 30 men, give or take). I had met some of the guys already in Basra 2008, so it was already a known quantity and the Company Commander was, coincidentally, a friend of a family friend. But that aside, I started off photographing every member of the company, about 60-70, I think. I knew that once out in Afghanistan, platoons would be separated into different areas of operation, and that I wouldn’t be able to photograph everyone. There were about 10 guys who I desperately wanted to photograph, but my allotted number of days was up and the MOD were unwavering in not letting me stay on for a few days or reapply to go back to Helmand a month later.

GALO: How does this series distinguish itself among similar temporal works related to combat and the military?

LS: The stories and images are about as far removed from stock pictures of “soldiers looking dusty, soldiers looking tired, soldiers firing, soldiers eating, soldiers running,” as you can get. Previous soldier [type] photo essays I’ve done have been on the domestic spaces, which again is far removed from the action. I guess I like to try and think about showing people things they don’t expect; things which are surprisingly mundane. If you read all the testimonies, you realize how bored some of the guys are as their area of operation is quiet. War is 10 percent action and 90 percent waiting, or so they say. We as viewers can be very lazy and just breeze through with a glance here or there, which is understandable given how many images we are confronted with every day. So, I think it’s important to challenge yourself as a photographer and as a viewer; to ask questions and look for answers. God that sounds pretentious.

Lance Corporal Sean Tennant, 29, Selkirk. Photo and testimony courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

First image: “I am looking forward to getting back and for the six months to be over. All this talk of being excited to get out there is rubbish. The younger lads will get a shock. I am going to miss flushing toilets and having a long shower whenever I want.” Second image: “I can’t remember how long I have been here. I was in Babajay before where our compound was under fire a few times. I wasn’t scared though, as I have been shot at plenty of times before in Iraq. IED’s are the biggest scare but it’s not a danger here. It takes a while to get used to that though — when you are on the ground you eventually realize that not every step you take is going to blow you up. So long as you don’t get complacent. My biggest worries are at home. I worry about how everyone is, if they are safe and that they are alright without me. I will be on my R and R for my son’s first day of school and I can’t wait.”

(Article continued on next page)