Artist of the Week 2/13-2/19: Lalage Snow Gives a Voice to the Faces Behind the War

GALO: What are the greatest challenges of the We Are The Not Dead series, considering its sensitive subject matter and being a woman in such a dangerous environment?

LS: Getting people to believe in it; even from the outset, almost everyone thought I was mad. I couldn’t GIVE it away when I finished [the series] in November 2010. NO ONE was interested in printing it or displaying it.

On a physical and emotional level, while working up to some of the “during” shots, I was on an operation with a unit whose task it was to antagonize the Taliban in the area so that the engineers could clear a route nearby. It was jokingly referred to as “Operation Certain Death” and “Operation No Return.” It was the first time I’d been on such an operation, and the buildup to the off was excruciating as I had no idea what to expect. The night before, I even wrote a goodbye letter to my family. The morning we were meant to leave for the “bad lands,” two soldiers were killed nearby. It’s a dreadful thing when it happens — and as a war tourist (which is what I am), all I could do was let the family unit of soldiers grieve as only they knew how: together. It was a horrible time — you feel like such an outsider; not all the empathy and sympathy in the world help to make you feel anything other than a stupid tourist for being there. During the operation itself, it was the first time I’d ever been in a firefight or had walked through a minefield. It was the first time for some of the younger soldiers too, and as such, the first time I saw genuine, raw, real fear in other people’s faces; the first time I pushed my own fear boundaries as far as they could go. I’ve been as afraid, if not more so, since then but was with another journalist and friend. On your own, it’s pretty dark.

Living conditions were, of course, harsh (I’d say it was survival, not living), and for two days helicopters were unable to do a resupply of rations. Stupidly, I had packed the majority of my rations in another bag which was delayed in being dropped, so all I had was a bag of fruit and nuts, a tracker bar, and mercifully, tea and coffee at the bottom of my camera bag. I was far too embarrassed to tell anyone and actually gave my tracker bar to a soldier who was going on patrol and looking more and more emaciated by the day, and who also didn’t have any food. We were drinking about eight liters of water a day, but we were still dehydrated. The Afghan soldiers were in the same compound as the Brits, but there was the usual “friction” between both armies; neither understood each other. The Afghans certainly didn’t understand what I was doing there: a girl; a girl without a weapon, and at one point they had a good grope while I washed my socks.

When I came home, my mother was a bit shocked. In three weeks I had dropped about a stone in weight and was just… just different for a while. And that was just after three weeks. These guys are out there for six months.

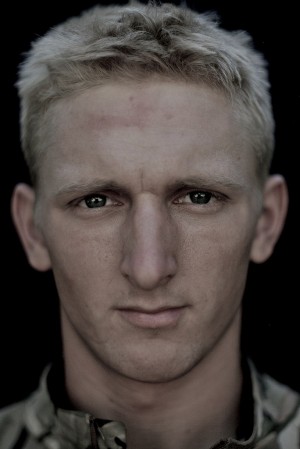

Private Becky Hitchcock, 23. Photo and testimony courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

First image: “My civvie friends think I am brave but I don’t see it like that at all. It looks so bad on the news but it’s alright really. I was scared just before leaving the UK – I didn’t know what to expect. I haven’t been scared here but I know there will be times when I will be.”

Second image: “The first casualty I dealt with was just a shrapnel wound, but the Afghan one this morning was serious. His eyes were wide open but his face was just white and I thought he was dead. But he grunted. Me and him were exposed to the firing, which was really scary but I managed to drag him on the other side of the ditch. He had lost his right leg above the knee – it had completely gone. His left leg, I went to pick it up around the calf but every bone was shattered. The skin of it was under his back, so I had to pull it down. It was thick like leather. It smelled…it’s a hard smell to forget. I can’t even describe it. Just burnt, rolling flesh.”

GALO: What are you trying to demonstrate or express by including the subjects’ testimonials; what do you consider is the responsibility you bear as someone photographing these soldiers?

LS: First, I believe that captions are very important to an image, be it a painting or a photograph, and believe that caption writing is almost an art in itself. I absolutely believe in the power of the written word; I’m an avid reader and occasional scribbler. As a journalist, you are always gathering interviews and quotes from sources, so the testimonies were just a natural thing to do and include. It’s part of who they are. As far as my responsibility is concerned, it is the same as anyone else’s: to be honest in one’s portrayal and depiction of a subject. When I had the idea in late 2009, soldiers were almost faceless and certainly voiceless.

A photo from the “Force for Change: Women of the Afghan Army” series. Photo Courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

GALO: You’ve said you’re lending a voice to servicemen and women who feel like they aren’t being heard. Why is it important that we listen to what they have to say?

LS: Everyone has a right to be heard — be it the guy who used to sell me cigarettes at the end of my street in Kabul, to the guy who installs the Internet, to the woman at the bus stop opposite, to whoever is reading this article. It just so happens that these young men’s voices are more relevant, for the moment, at least. And the perception of what life is like out in Helmand Province is 100 percent formed by what we see on the news, which is dramatic, war-like, dusty and dangerous.

But that’s footage taken by a news team. What do the actual soldiers make of it all? Right now, and in years to come, people are and will write books about the British military in Afghanistan; they might have been there themselves, they might talk to people who have served there, but the testimonies by soldiers in We Are The Not Dead are the soldiers’ right then and there, saying what came naturally, explaining what happened when an IED went off just half an hour ago, describing it in real time, missing home, being hungry, being scared, being bored, being human. Ask the same soldier to describe what happened then now, two years on and I’d bet money that a lot has been forgotten.

A photo from the “Force for Change: Women of the Afghan Army” series. Photo Courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

From 2007/2008 to 2010/2011 people actually cared about what was happening in Afghanistan. Now no one gives a damn — foreign troops will leave and so will the world’s press. Afghanistan will descend into chaos once again, but hey, there will be no journalists or soldiers there, so it won’t be widely reported or documented, and no one will really care.

(Article continued on next page)