Artist of the Week 2/13-2/19: Lalage Snow Gives a Voice to the Faces Behind the War

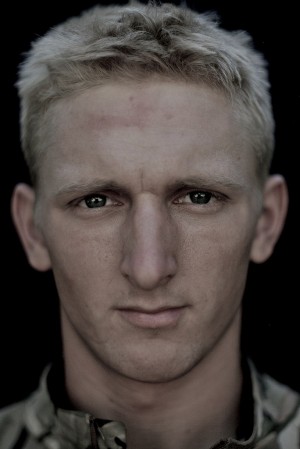

GALO: How do the We Are The Not Dead images speak louder than words?

LS: The images are basic. I’m not pretending that they are fantastically well shot and worthy of great accolades. I don’t know if the images DO speak louder than words. I guess the viewer is forced to look into the subject’s eyes, as with any portrait, be it a Rembrandt self-portrait or a classical bust you, as a viewer, are forced to examine the face in front of you, and to listen and see if it speaks. It’s a triangulation of viewing, I suppose. Again, that sounds pretentious, and it’s not meant to. You HAVE to read the captions though. Without the captions, I don’t think the full impact can be understood. But people’s reactions have taken me by surprise. I’ve never tried to be reactionary or particularly radical, I just like telling stories firsthand be it through film, photography or writing. I’ve had some people write hate mail and text messages calling me a propagandist, which made me laugh. I’ve had others accuse me of stealing someone else’s idea, which also made me laugh. It’s ludicrous. If you met me, you’d realize I’d NEVER do that, and it wasn’t particularly original in the first place. I’ve had other people — soldiers from other countries, retired soldiers, parents of soldiers, other photographers and artists — write and say how much they like the series. You can’t please everyone, but as long as you remain honest to your subject, that’s enough.

GALO: Overall, is the series intended as a positive or negative depiction of combat?

LS: Neither, it is what it is. It is up to the viewer to make of it what they will. Having lived with soldiers as a war tourist, I have an inkling of an understanding of their lives as a military family — as brothers in arms, as men in combat, and how different life is back in this country when all that is stripped away. And as such, I have an inkling of an understanding about PTSD. Heck, live in Kabul for two and a half years and you can’t not understand it. I’d hoped that by reading the personal testimonies of the individual soldiers that even the most anti-army, anti-war, anti-soldiers viewer might in some way find a way to empathize or understand.

A photo from the “Force for Change: Women of the Afghan Army” series. Photo Courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

GALO: Because you are a woman putting yourself not only in the danger of combat, but also within the gender inequity of the Arab world and Afghanistan, did you experience any prejudice? And how do you explain your interest, which many may consider unusual for a woman in particular, in combat and warfare?

LS: I grew up fairly tomboyish and in a military family, so combat or war was never “The Other.” People always ask me why I do it, and I struggle to find a decent answer. Part of it is the adventure, the adrenaline, the being in the thick of it, of being part of something monumental. Part of it is wanting to witness things firsthand; to help tell people’s stories, to give people a voice. I’ve been a storyteller for as long as I remember, so I guess that counts for something. I’m curious by nature and nosy. If something is happening in some far-flung corner of the world, I want to be there — to see things firsthand, to hold a magnifying glass on something, to make people wake up and act. I loathe apathy. I’m also well aware that I was brought up with privileges and am incredibly lucky by birth. So, in some way, I feel a strange duty to help others by showing the rest of the world how things really are. My first photo-essay as a student was on a Council Estate in South London where there had been a lot of gun crime. The press was all over it, but the story became distorted and the residents of the estate were angry at being misrepresented. It was only a student project, so it didn’t come to much, but I got to know the other kids involved in crime, and I got them and the other residents to trust me. At the time, I was passionate about giving them a voice. That’s what it comes down to, giving people a voice.

A photo from the “Force for Change: Women of the Afghan Army” series. Photo Courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

And people always ask about the gender thing. Yes, it is a boys club in some respects — most of the photographers I know in Afghanistan are guys; when I was a stringer in Bangladesh in 2007-2008, I think I was the only foreign female photographer. It can be a bit grating when you overhear macho talk amongst photographers, but I’m sure it’s the same in any industry — finance, law, TV, cooking, trading, painting, civil service…It is still a man’s world in many ways, but all you can do is keep doing what you are doing, and don’t get too caught up in the gender dialogue. There’s not much you can do about it anyway. You are born what you are born and a photographer is a photographer. There are benefits of being a man; there are benefits of being a woman. Ultimately, it comes down to your own spirit and approach to a subject. Perhaps I’m being naïve. I do sometimes wonder if I’d get taken more seriously as a guy, but maybe I’m just making excuses.

GALO: Could you describe the work you’ve done in partnership with Save the Children and Women for Women International; why did you get involved?

LS: I was based in Afghanistan for two and a half years until a few weeks ago, working as a freelancer and picking up work from all sorts of organizations; from stringing as a journalist for newspapers to photographing and filming for NGOs. The funny irony is that although women’s rights in Afghanistan are almost the worst in the world, international organizations often prefer to use female photographers as we are “allowed” to photograph women and children without causing too much offense. In any case, western women are considered to be the third gender.

A photo from the “Force for Change: Women of the Afghan Army” series. Photo Courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

GALO: What is your current project in Kabul, documenting women in the Afghan National Army? Does it share a similar inspirational basis and photographic approach as the We Are The Not Dead series?

LS: It came out of the We Are The Not Dead series as I heard about women being trained while I was on my way out of operational theatre at Kandahar airbase, having just shot the “during shots.” But no, it’s very different. It took a year to get the access — which is why I moved out to Kabul in 2010 — and then six months to film. It was my first full-length film, and as such, a real learning curve. It was hard, hard work, and at times, incredibly lonely — being stuck out on an Afghan military base on the outskirts of Kabul, sharing a dormitory with 14 other girls whose language I didn’t speak (although I learned to understand it very quickly!). I was very close to giving up on so many occasions; filming and photography are totally different trades so it takes time to get used to either discipline. But I suppose in “approach” it is similar to We Are The Not Dead. I got to know my characters like sisters, which is why they gave me such intimate access into their very closed-off world. Afghan girls are not encouraged to speak publicly, be radical, be different, and to be filmed is akin to drawing so much attention to yourself, you might as well be a prostitute. With the soldiers in We Are The Not Dead, I spent so long training with them that they got to know me as much as I did them. And with both projects, I didn’t force anyone to be part of it if they didn’t want to.