Broadway Posters: A Window to the Great White Way

When you first step over the threshold into the Triton Gallery on Ninth Avenue in New York City, you better catch your breath and take a peek at your shoes — they may have turned red in the instant. It’s an unassuming enough office space but the walls are alive with all the color and magic that a Broadway show can deliver. You’ve arrived in show business Oz. Now all you have to do is find the wizard…

That proves easy enough. A tall, red-haired man steps forward with all the good cheer of Ray Bolger’s scarecrow in the classic film and introduces you to the wizard himself, otherwise known as Roger Puckett. If you’ll forgive the pun, he’s a soft-voiced gent with a puckish glint in his eyes whenever your own eyes alight on a particularly arresting poster.

Fresh from the recent Tony awards, a few familiar images instantly greet the eye — Nice Work if You Can Get It, featuring a whimsical caricature of Matthew Broderick in Kelly O’Hara’s arms, Tracie Bennett striking one of Judy Garland’s memorable poses from End of the Rainbow, and a street sign graphic, powerful enough, if a bit ho-hum for Clybourne Park, the final winner in the straight play category. Have the Tonys given Triton Gallery a jump start for the summer?

Puckett’s enthusiasm is almost infectious. “They’re a godsend. The rush of sales follows the Tonys but happens before as well. The Tonys stimulate business just by being and it’s the end of the season. Then there [are] the TV ads on CBS, showing graphics on the shows. People can Google the posters.” But sometimes there are reversals in one’s early expectations. One such leap that fell short was Leap of Faith. “I sold a lot of posters. It was a very expensive show and it had a sad closing.” (Ben Brantley from The New York Times delivered a quick axe blow to this one.)

One show that came and went with a resounding clunk was Kelly. Produced by David Susskind, a wunderkind of ’50s television and a real risk-taker, it closed after one night. It was the first show that ever lost close to a million dollars. Could it have been the subject matter? A musical about a man who jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge may not have been for everyone’s palette. Another one that closed unexpectedly, and was released after the film, was Breakfast at Tiffany’s with Mary Tyler Moore and Richard Chamberlain. Perhaps Audrey Hepburn’s interpretation of Truman Capote’s Holly Golightly said all that needed to be said about runaway vixens that capture the heart.

But it’s high time to enter the happier moments and magic of the past…

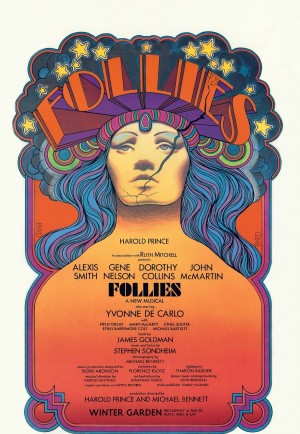

One of the first images that seduces is from Follies, with artist David Byrd’s gorgeous art nouveau caricature of a star facing the viewer head-on. According to Puckett, “the image was taken from a picture of Marlene Dietrich putting on makeup with her hair pulled back in a skullcap.” Few will recognize the film star from Byrd’s interpretation, but the classic goddess he’s created reads loud and clear.

Before you can blink, Nick van Hoogstraten, Puckett’s business partner encountered earlier, turns my attention to the artist’s original graphic for J.C. Superstar. For anyone old enough to remember, all the memories of that ’70s show-stopper will come flooding back at the sight. Created for the album cover, the eponymous savior with his psychedelic halo is unmistakable and as my host is quick to point out, the two golden angels facing each other in a U-shaped design on the bottom became the singular image used for the eventual Broadway production. It’s little wonder, as this angelic duo could easily have been translated into a pin worthy of Tiffany’s windows.

Interestingly enough, to Puckett the real stars on the walls are the poster artists themselves. There was a certain reverence I detected in both men when they spoke about the creators of this oft-neglected art. In earlier gallery exhibitions, Byrd and other graphic artists have autographed posters for Triton’s customers. In one instance, Byrd complied by offering the first sketch from Follies to his fans.

Puckett and van Hoogstraten explained how Byrd came to prominence designing posters for the Fillmore East impresario Bill Graham. From 1968 to 1973, Byrd created the posters for Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead, among others. Taking on Jesus Christ — the Superstar of them all — as his next challenge must have seemed a natural step up.

Godspell was another iconic poster — it would seem Byrd was under the spell of religious celebrants, or was it the other way around? There was a revival of the show that my two experts were more than willing to share, where the head from the original Godspell, with its serpentine locks of hair, is superimposed over a brick wall with a young boy walking by — caught in mid-step by the gigantic image. It’s a style that brings to mind the early show bills promoting Sarah Bernhardt or the decadent flourishes of an Aubrey Beardsley, but in Byrd’s hands, it translates perfectly to modern times.

We talked about Hair, another iconic image that became synonymous with the age of the flower children. It’s ironic that thousands of young people nationwide embraced an image of that electrifying head of hair, individuals who may never have paid for an actual theatre ticket. This poster utilizes a reversal technique that was later used by Richard Avedon for the Beatles. Its artist, Ruspoli-Rodriguez, keeps one half of the blazing Afro head in a negative format, with the other half positive. It is unbelievable to discover that this was the only poster produced by this talented artist. No theatrical producer hired him to create his singular magic again.

“He had a wonderful eye,” Puckett recalled. “He was a very talented man. He did some work at the time for Esquire Magazine, [and] then he just…disappeared.” It was also a time when the AIDS epidemic took many talented lives. But we agreed that was only speculation and the artist’s fate must remain a mystery.

How did this love affair with the theatre poster begin for Puckett? Did it start with a private collection perhaps? He countered with a resolute “no.” “I started the gallery in 1965 on 45th Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, as a frame shop, and the posters became a nice way to sell frames.” (Puckett had made enough money as a dancer in the 1964 World’s Fair in New York to buy the store and soon after, started his own business.) Directly across the street from the Hirschfeld (formerly the Martin Beck theatre) it had two large front windows where he could display his posters. “People didn’t know exactly what I was doing at first. They’d come in and want to buy tickets for the show and I’d have posters of old shows that had already closed. ‘Where’s that show running?’ they’d insist, ‘Where can I see it?’”

(Article continued on next page)