‘Far From Heaven’: The Music of What Happens

To most, the Fabulous Fifties bring to mind images of girls in poodle skirts and pancake makeup, diners and juke boxes, a time when Elvis first gyrated into our living rooms on TV and being named prom queen was the life goal of every nubile cheerleader. It was a period of ease for America: we had no wars and there was endless prosperity, access to good food, good education, good housing, good jobs and good times. But like with every colorful picture there are the real stories that go beyond the pretty facade and much closer to the complicated truth of being human, and this is what the new musical Far From Heaven is all about.

Far From Heaven is not a new story. Ten years ago, Julianne Moore played the lead in the Todd Haynes film, an attractive Connecticut housewife, Cathy Whitaker, a woman decked out in lustrous, jewel-colored clothes that looked like they were ripped from a magazine cover and yet, despite the Stepford wife elegance, still able to serve dinner on time each night. Her whole life was spent engineering, with other like-minded female spouses, the social underpinnings of their husbands’ upwardly mobile corporate careers: the 2.2 children, the car pool, the local society page and the landscaping, as if they were directing an epic in which their families starred. The film was saturated with autumn color as though it were to distract the eye from the bleakness beneath the bright, dying foliage: that Cathy’s husband, Frank, far from being a stalwart working man and devoted partner, was hiding the deep dark secret of his homosexuality; and that his emotional distance had caused her to look elsewhere for solace, and not in a place anyone would have guessed, but to Raymond Deagan, the gardener, who happened not only to be intelligent and emotionally available, but a black man to boot.

The musical, with a book written by the very talented Richard Greenberg (Take Me Out, about a gay baseball player, among his best works) and music and lyrics by Scott Frankel and Michael Korie (the team that brought us the fabulous Grey Gardens a few seasons back), does not stray far from the film’s story line, but rather takes it into another realm. Here, the music becomes the color, the fall theme (beauty just before death) addressed visually by leaves drifting onto the stage at various intervals. The songs and background pieces move from the soaring, dramatic gestures of a good ’50s film soundtrack, as in the set-up instrumental piece that opens the play, to very personal, more contemporary and intimate ballads such as the beautifully insinuated “Miro” which is sung with the gardener when they unexpectedly meet at a local art exhibit, and the final scene, where our heroine makes peace with her new life, alone and center stage with “Autumn in Connecticut.” The music fits the story like a very well-made and tailored piece of clothing, like one of Don Draper’s suits in Mad Men. This is not a surprise, really: Frankel studied years ago at Yale with Maury Yeston, who wrote the music for Nine, and embodied that Fellini-esque world with each ebullient note. Frankel, a more forward-thinking and personal composer, learned that lesson immaculately and takes it here into much more treacherous emotional territory.

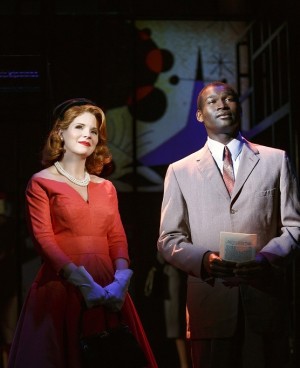

And then there is the cast. It is safe to say Kelli O’Hara is the reigning Queen of the Broadway Musical. As Cathy, she walks a tightrope between the breathless euphoria of the time and the deep disappointment that awaits her, but not until confronted with it head on, after unsuccessful psychiatric intervention and Frank leaving her for a man, does she know she is in free fall. Having gone off with the gardener for an innocent afternoon lunch, she is spurned by her suburban wife neighbors amid jokes that she is “nice to Negroes” (played with superb bitchiness, especially by Sarah Jane Shanks in the dual roles of Doreen and Connie, who turns the shirtwaist dress into a deadly social weapon) and, finally, even by the gardener who, because of the local hoopla over his “conversations” with Cathy, has to leave town. O’Hara cannot sing a note that doesn’t hit a listener in the solar plexus — you feel an immediate connection with whatever she is doing and an attendant empathy. She wears the rounded ’50s silhouette with perfect poise and again shows her range, as this role is so unlike, say, the waif she played in Light In The Piazza. She holds that stage in the final moments and brings the audience to their feet to rally around her. And so, with all the upheaval, in the end there is hope.

Kudos also to Isaiah Johnson as the gardener who has to choke on his feelings for Cathy in a very white suburban Connecticut, and does it with more dignity than the people chastising him; and to Steven Pasquale as Frank, whose will to adhere to the morals of the time almost kills him and whose bravery sets him free, although he sometimes disappears into slight caricature. The set is very versatile, but perhaps too darkly lit so as to hammer home the show’s serious core idea, although this becomes less of a distraction as the play progresses. In the audience this night was Lindsay Andretta, who played the Whitaker’s daughter in the Haynes film and is now a musical theater actress. “I had such a good time playing that role, but I had no idea it would follow me here to Broadway!” We, on the other hand, think such a good story with its universal message against bigotry should have made it here long ago.

“Far From Heaven” is currently playing (through July 7th, 2013) at the Mainstage Theatre at Playwright Horizons in New York City, located at 416 West 42nd Street (between 9th and 10th Avenues) New York, NY 10036. Ticket information for the production can be accessed by visiting Ticketcentral.com or by calling (212) 279–4200 (Noon–8 p.m. daily).

Featured image: Pictured (L-R): Kelli O’Hara and Isaiah Johnson in a scene from the Playwrights Horizons production of the new musical “Far From Heaven.” Photo Credit: Joan Marcus.