Photographs of Things Past: Eugène Atget at the MoMA

Abandon hope, all ye who enter the Museum of Modern Art’s current show Eugène Atget: “Documents pour artistes,” devoted to the work of French photographer Eugène Atget (1857-1927), if you expect to sigh over perfectly-composed, postcard views of the Eiffel Tower or the Arc de Triomphe. Atget took 8,500 photos in and around Paris, yet not once did he ask that city’s most iconic structures to smile and say fromage. Atget stubbornly eschewed the historically-weighty monuments and boulevards that came to define the look of the capital, turning his camera instead to her empty streets, soon-to-be-demolished buildings, and to the stalwart tradespeople, merchants, and prostitutes who failed to make it into the pages of toney tourist guidebooks.

Organized by Sarah Hermanson Meister, curator of the Department of Photography at the MoMA, “Documents pour artistes,” pulls Atget out of the pages of the coffee table tomes which have long been the primary sources of our knowledge of the photographer, and displays on the walls of the Robert and Joyce Menschel Photography Gallery, the sophisticated and truthful vision that defined his output.

The Bordeaux-born Atget settled in Paris in the 1890s. He had limited experience in the visual arts, but saw photography as a way to make a living and began selling his photographs to other artists in the nearby town of Montparnasse, advertising his work as “documents pour artistes” (“documents for artists”). As it was common practice for artists to paint scenes from photos, Atget decidedly hit pay-dirt once he had purchased his first camera around the mid-1890s and embarked on the métier,which would support him until the end of his prolific life.

Atget photographed Paris with a large-format wooden bellows camera fitted with rapid recti-linear lens. The images were exposed and developed as 18×24 cm glass dry plates, a few examples of which are included in this show. Each print was made by exposing light-sensitive paper to the sun in direct contact with one of the negatives that the whimsical French photographer numbered sequentially, often scratching the number of the emulsion on the negative, and in effect, having it appear in reverse at the bottom of the print.

Many of Atget’s photos also reveal what became his favored technique of vignetting, where light coming through the camera’s lens does not fully cover the glass plate negative, which allowed him to create an arched pictorial space that echoed the physical one and may have existed in the photographed subject itself.

Taking its cues from the photographer’s method of organizing his work (which was as much for the convenience of his clients as for himself), the show has compartmentalized Atget’s work into six distinct groups (such as shots of the Avenue des Gobelins and the imposing Parc de Sceaux), bringing into focus (no pun intended) his specific interests in locations, objects, times of day, and the figure.

The shimmering beauty of a photo such as 7, rue de l’Estrapade, where early morning sunlight emblazons the sinuous curves of an iron stair railing, has the power to suspend our breathing. And Coin, Boulevard de la Chappelle et Rue Fleury 76, its curtained doors flanked by two sturdy females, exudes both solemnity and discomfort. Both works are emblematic of Atget’s style, wrought by the photographer’s particular choices (such as shooting in the early hours before human activity set in); and it is those very choices that have imparted his work’s spaciousness and ambience and wherein lies its timelessness.

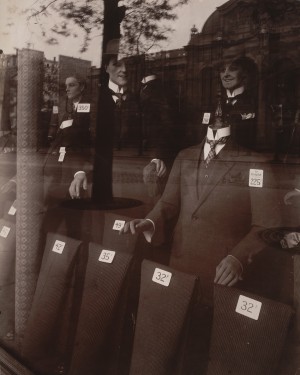

Long fascinated by store window displays, Atget took many shots of the elegant or jauntily-attired male and female mannequins placed in those vitrines, and the series of gelatin prints of the 1925 Avenue des Gobelins displays both mystify and entice the viewer, as much as the mannequins seem eager to break out of their glass confines into a world they can never share.

Photos such as these made Surrealist artists sit up and take notice of Atget’s work, detecting in them his sensitivity to the off-beat and eccentric.

And then there is Sceaux, the enormous abandoned park on the outskirts of Paris, which Atget shot 66 times from March to June of 1925. Sceaux is the locus where Atget becomes Atget. Sepia-toned shots with their wispy, drawn-out sense of light (due to long exposures) capture crumbling or beheaded statuary and silent and overgrown paths, soaking the images in a deep bath of nostalgia and longing.

As the late John Szarkowski (who was Director of Photography at MoMA from 1962 to 1991) noted about Atget’s work at Sceaux: “One might think of Atget’s work at Sceaux as…a consummation and as the consummate achievement of his work as a photographer – a coherent, uncompromising statement of what he had learned of his craft, and of how he had amplified and elaborated the sensibility with which he had begun. Or perhaps one might see the work at Sceaux as a portrait of Atget himself.”

After the restoration of Sceaux began in June of 1925, Atget stopped photographing it, perhaps perceiving that the effort to tidy the grounds for its conversion to a public space would alter its untended and decaying grandeur.

Mailmen, rag pickers, gypsies, and prostitutes, bring up the rear of the MoMA show detailing Atget’s figural work. Here itinerants and transgressors are honored and immortalized, shot full-length, surrounded in an Atgetian haze or with sharp contours. A group of zaftig whores smiles directly at us, indistinguishable from any other bunch of bourgeoises who could just as soon turn out a good coq au vin as they could turn a good trick. A young girl throws out her arms exuberantly while an organ grinder plays. Each figure was a unique being, soon to evaporate through the encroachments of modernity.

To those unfamiliar with Atget’s work, MoMA has done well by them, having unfurled in its show some of the photographer’s best examples from his enormous body of work. Atget’s considerable work in figural photography is particularly noteworthy, revealing a side of his oeuvre either little known or outright unknown. No complaint can be leveled as concerns the clarity of label notes and organization of the photos. The simple black frames holding each image and set against the gray walls of the Menschel Gallery, ensure that the viewer will give undivided attention to these works and to the man behind each one. Atget would have approved.

So – Eiffel Tower anyone?

The Eugène Atget: “Documents pour artistes” exhibition may be viewed through April 09, 2012 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. For more information regarding the exhibit, please visit www.moma.org.