‘Picasso: Black and White’ and All the Shades of Gray

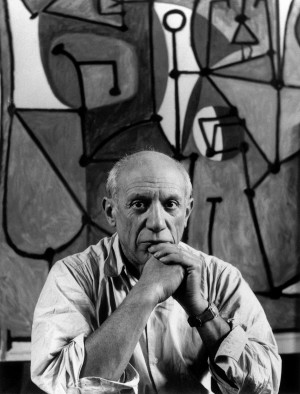

Ambitious, brilliant, challenging, daring, enlivening, formidable — you could go through all the letters of the alphabet and not exhaust the number of adjectives for his genius. His style and subject matter encompasses all the shades of gray from black to white and then some. If you don’t believe it, try throwing away all the colors of the rainbow and see how many artists are left standing: Pablo Picasso and he’s 10 feet tall.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum has mounted an unprecedented show, Picasso Black and White, that proves what true genius can do with a piece of charcoal or a smattering of black and white paint. From his earliest Blue and Rose periods, his pioneering and iconoclastic investigations into Cubism, his neoclassicism figures and forays into Surrealism and his historical nods to past masterpieces and later sexually-themed canvases, a devotion to a monochromatic vision emerges as central to Picasso’s career. The curator, Carmen Giménez, is no stranger to her fellow countryman’s prolific works, having organized an impressive number of exhibitions for the artist here and abroad. (She was recently inducted into Spain’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts as Academician of Honor, the first woman to hold that title.)

The Guggenheim’s space is ideal for showcasing an artist’s lifetime journey. But to encounter 118 paintings, sculptures and works on paper from 1904 to 1971, the viewer will have to decide whether it’s better to spiral upward or downward, circling the six rotunda levels on a dizzying path, whatever the choice. Is a traditional path of progression best, from youth to the twilight years, arriving at last to your own epiphany of his talent? Or should you hasten by elevator to the top to view the surprisingly fresh and whimsical image (The Kiss) from 1969 of a couple with lips melded together as if with hot glue, then descend downward through the decades to the impassioned anguish of Woman Ironing?

Let’s start at the beginning — he deserves it — and hazard the climb, with a few loops along the way.

A little disputed masterpiece from Picasso’s Blue Period is Woman Ironing from 1904. Its somber gray colors only heighten the sense of an emaciated soul, broken by life itself. Even the white tones of her shoulder jutting upward accentuate the gravity of the rest of the body falling away. This painting is in the Guggenheim’s permanent collection and worth seeking out. Its power is on an equal footing with Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters, another monochromatic study of the downtrodden. Inspired by Picasso’s visits to Saint Lazare, a women’s penitentiary, its subject was well-known by the young artist’s friends and thought to be an occasional mistress to Picasso himself.

When it came to an understanding of the depths of human suffering and how to articulate it through art, Picasso was old before he was young. He found solace in France, outside his own country, driven by a hatred for the horrors of Franco’s regime. Unfortunately, he died a couple of years before Franco’s own demise. Arguably, his greatest creation, Guernica, will remain as a lasting testament against the senselessness of war. That massive monochromatic work is in the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection, but this exhibition focuses on several 1937 images from that work, for instance, Mother with Dead Child II and Head of a Horse, Sketch for Guernica. The latter is particularly powerful in delineating through the upturned head and the open mouth with its dagger-like tongue — in an almost child-like rendition — what death must be like. The devil is in the details, as someone aptly said.

Curator Carmen Giménez, in the wall notes provided, speaks about Picasso’s universal perspective in his images: “To become a great artist understood by everybody, it is necessary to shake off every speck of nationalist dust as Picasso managed to do and in doing so, he has obliged all of us to follow his path.” Such gems of wisdom could be easily overlooked as one moves from one rotunda to another, as they are placed, almost as an afterthought, in side alcoves when winding one’s way from one level to the next. If the picture is everything, there’s no easy answer to this dilemma, especially when displaying an artist of such virtuosity and output. Audio sets are available, however.

Another later canvas from 1944-45, The Charnel House, purportedly deals with the Nazi genocide but was based primarily on photographs of a slaughtered family during the Spanish Civil War. In such works, it is the stark intensity from minimal tones, the obvious contrasts of dark and light that add immeasurably to the subject’s power.

The wages of war and violence would follow Picasso all his life, and at the advanced age of 82, he would create several versions of Rape of the Sabine Women. This was an old story, set in the early days of the Roman Empire, when Romulus invited the Sabine people to a festival with the intent of stealing their young women for marriage to Roman soldiers. Inspired by Nicolas Poussin’s painting of the subject, Picasso would do several versions. Obviously a heated topic with sexual overtones, it also was considered fitting to interpret by the likes of Jacques Louis-David, Peter Paul Rubens and sculptor Giambologna. The exhibit painting’s terrible poignancy derives from the upside-down positioning of the distraught mother in the bottom foreground with child, and looming overhead the menacing rider, dagger raised, on what appears to be a demon steed.

But all is not doom and gloom in this remarkable exhibit. Notwithstanding his singular devotion to his own vision, however dark it might be at times, Picasso was never afraid to pay homage to the artists of the past — especially the Spanish masters like El Greco, Francisco de Zurbarán, Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, whose use of blacks and grays were often predominant. Picasso’s The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velázquez) is on loan from the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, and Ms. Giménez is to be commended for its inclusion. This painting (and many others on display) utilizes an age-old technique known as grisaille, in which uses of various tones of a single color, ie. gray, produce a three-dimensional effect. The Velázquez version in the Prado Museum in Madrid is a magnificent work from 1656 that mesmerized Picasso. It’s great not only for the richness of the human landscape, the central position of La Infanta, the young princess with her doting maids and the intricate set detail of the room in the royal household of King Philip IV, but for the amazing perspective of the figures, from Velázquez himself, the Royal couple reflected in the background mirror, and the dark silhouette of a man with cape in the far background. The Picasso version has kept to the original players but his version is a kind of cartoonish allegory as only Picasso can produce — all the pieces of a pictorial puzzle strewn haphazardly about and reassembled. A well-placed print of the Velázquez, as well as the Poussin Rape mentioned earlier, for example, would go a long way toward elucidating Picasso’s respectful but revolutionary departure from his artist predecessors.

(Article continued on next page)