Reading the Tarot: The Legacy of Salvador Dalí

The Contemporary Deck

In curating the 21st century contemporary deck, Stacy Engman hand-selected an artist or fashion designer for the card representative of his or her artistic iconography; the only restriction was the size of the paper. The exhibition is installed in the Raymond James Community Room of the Dalí Museum — an unadorned, vacuous space with one enormous outer wall of glass overlooking the exterior gardens. It is a quiet place where one can contemplate the mixed media show much as one would during an actual tarot card reading. There are photographs, photomontage, collage, oil and pencil representations in neons, pastels, black and whites and the distinct palette of Dalí.

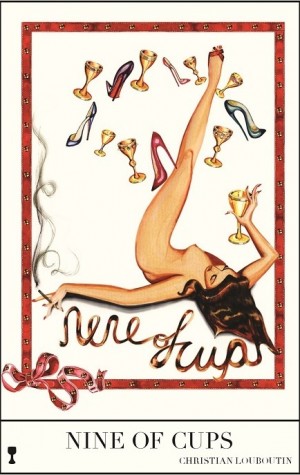

Some cards, like Japanese Pop artist Yoshitomo Nara’s Four of Swords, keep to tradition by including each suit and according number of objects, while others, like designer Christian Louboutin’s Nine of Cups, nods in the general direction of tradition but also adopts the fanciful nature of Dalí (there are only eight cups swirling about his signature stiletto heels alongside the leg of a voluptuous nude woman), and still others, like portraitist Kehinde Wiley’s Nine of Coins/Pentacles, omit all reference to the suit and number drawn.

One of the more memorable pieces is the Knight of Wands, a poetry collage by Turkish artist Haluk Akakçe. In pencil, Akakçe offers the recipient of the card a poem, “Like the frog prince whose (sic) waiting to be kissed / the Knight of Wands is always there for you, waiting patiently. / After all, magic only works when one has faith! / Be worthy of it / and he will give you the universe.” Below the verses is a 24-carat diamond and ruby broach in the shape of a frog mounted to the paper. His card is a contemporary interpretation of Dalí’s card, in which the knight rides his horse atop a photograph of a bejeweled frog.

The iconography is most strongly at play when one is well versed in either the contemporary artist’s oeuvre or the image rendered into the individual card. Take, for example, Queen of Coins/Pentacles by German artist Josephine Meckseper. A woman, dressed in 1970s hippie attire, walks down an urban street, her arms overburdened with shopping bags. The tension between peace and love swinging as a necklace around her neck challenges the commodification of a society inundated with strip malls, 24-hour shopping networks and Rodeo Drive. In Karl Lagerfeld’s self-portrait, King of Wands, he reclines in an egg-shaped chair — at once synonymous with power and Dalí’s own leitmotif of the egg found in many of his artworks. The Hanged Man by Patrick McMullan is an upside down photograph of Andy Warhol (Warhol as the Invisible Sculpture at Area, NYC, 1985).

Most reminiscent of Dalí’s deck is contemporary surrealist Francesco Vezzoli’s Queen of Swords, subtitled, Study for a Portrait of Lana Turner as Judith, Queen of Spades. Just as Dalí used old-world art in his tarot deck, Vezzoli superimposes Turner’s head over Judith’s in Vincenza Catena’s 16th century oil painting, Judith, with the iconographic image of her holding the sword that she used to decapitate Holofernes.

There seems to be a crafty wink to Dalí’s motifs in most pieces, whether it be his fascination with women’s breasts (appearing as a montage of ceramic coffee cups in the shape of a grand pink breast), or his penchant for androgynous figures (a black and white and red figure wearing men’s underwear and a tight-fitting garter belt), or the gore of humanity (the stabbing and decapitation of men).

It would be interesting to know Dalí’s thoughts on the exhibition. Dalí — the Catalan who challenged others to follow in his footsteps by breaking the modality of acquiescence, approval or obedience. Undeniably, there are a few cards in the deck that appear at face value to be a blind favor from the curator or, perhaps, just a bad day at the easel, with neither rhyme nor reason to the history of the tarot card and Dalí’s own contribution to the art form. But those might, in fact, be the ones that Dalí would like best — the pushing of the envelope; the refusal to fit into any deck of cards. For Dalí, to be true to one’s artistic direction, is to be true to one’s self, even if it doesn’t point north, south, east or west.

And if there were one criticism of the collection, it would be that — how seemingly disjointed it is. It is at times jolting to look at so many disparate images hung so closely together. The mind races and paces, trying to divine coherency. And, yet, that is the success of the show — artists and designers from around the globe coming together to honor the incoherent life and works of Salvador Dalí.

(Engman’s deck can be purchased from the KLÜP Foundation, which funded the show. )

The Dalí Legacy & His Serendipitous Museum

A yellow page search of establishments providing tarot card readings in St. Petersburg, Florida renders 60 hits — not bad for a city with a population just shy of 250,000. There’s little data on who frequents such places, but, to be sure, the Gulf Coast city is a place as wild and outlandish and cultured as Dalí was.

St. Pete’s — as the locals fondly call it — is a tourist destination best known for its beaches, magenta sunsets and kitschy, old-Florida boardwalks and rickety motels. But it has much more to offer than watered-down mai tais served in plastic cups and the pervasive deep fried grouper sandwich.

The waterfront locale has a vibrant downtown, where one could spend an entire weekend visiting museums and art galleries, drinking fine wines, indulging in exquisite gastronomy from around the world and listening to live music. Amongst the Museum of Fine Arts, the Chihuly Collection and the Florida Holocaust Museum sits the city’s gem: the Dalí Museum — with over 2,100 works. It is the world’s largest Dalí collection.

(Article continued on next page)