Take Five: Design Team Haas & Hahn Paint an Entire Favela

Eight years ago, artists Jeroen Koolhaas and Dre Urhahn (collectively known as Haas & Hahn) traveled to Brazil, specifically to Rio de Janeiro’s slums, to shoot a film about its hip-hop culture. Stacked high like tin cans, these villages are the color of rust and threaded with clotheslines. After spending time in several of them in both Sao Paulo and Rio, the two were struck by the creativity and optimism that wove its way through each village. This energy sharply juxtaposed the widespread negative opinion of the lives of their inhabitants.

Could this be changed through paint? They thought so. They told GALO that “staring at the rolling hills, covered with brick houses, we came up with the idea to make an immense painting on a favela.”

Using bright strips of primary colors and vivid geometric shapes that recall Cubism, the occupants could force outsiders to rethink their notions of favela-life. After researching the area extensively, the artists pushed their careers to the side and hopped on a plane to Rio. It was here that Boy With Kite was born. The simple portrait of a child flying a kite symbolizes the children of the favelas.

The project has since grown, spreading its color into a New York art gallery and to a dilapidated neighborhood in Philadelphia. Through a successful Kickstarter campaign (garnering $116,655 in total contributions), Haas & Hahn have raised enough money to return to Rio in April 2014. Using a style that blends architecture, murals, graffiti, and traditional painting, they hope to saturate an entire favela with color. In doing so, they seek to harness the power of individual communities so they can create positive change internally. By beautifying on the outside, they hope to fuel the soul.

In an e-mail interview with GALO, the artists expanded on their goals and process.

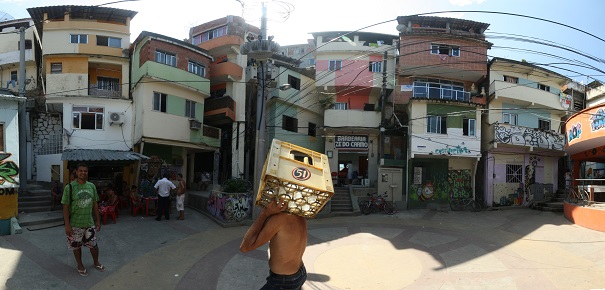

Pictured: Praça Cantão. Photo Credit: Haas & Hahn.

GALO: You typically train local artists to paint the favelas. What training is required for the painters to complete the project? How much individual inspiration goes into the project and what do you hope painters draw from the experience?

Haas & Hahn: Local people and youth are trained and hired to become painters. They aren’t necessarily artists. They receive instruction on worksite conduct and safety as well as specific training on how to plaster and use scaffolding, general paint skills, brush-use, workflow, and job and media training. [They also learn] basic English.

We make most design decisions together with the building owners and [the] users. We go door-to-door and talk about the project, discussing their preferences. It’s a very long process, but the only way one can afford to go to someone’s neighborhood with such an immense project. It has to become everybody’s project first.

A sketch of one of the favela neighborhoods to be painted. Photo Credit: Haas & Hahn.

GALO: What is your intended effect on the neighborhoods with the painting? The neighborhoods transform from shanty towns and slums into living artwork via bright colors and eye-catching patterns, but do you hope to inspire members within the neighborhood or visitors outside of the community? Have you noticed any positive change within the painted communities, such as decreased crime or increased tourism?

H & H: The effects of a project on the participants will be different for everyone. Some might become inspired and become passionately involved in the subject. Some like the work but might not necessarily be interested in the processes. At the same time, they feel it’s special. Some like the scale, others start talking about the psychological effects it has on the passersby, and all are as impressed or surprised with the results as we are. It’s great to work on something that creates a completely different dialogue than people are used to having. It’s very refreshing for everyone.

Tourism has created jobs and local commerce has picked up, but it’s hard to quantify long-term results as it would involve studies that may be more expensive than painting a few houses. From our perspective, the greatest success is when — upon realization of the projects — the media for once says something constructive and positive about the neighborhood and its people. If that helps to change outside perception even a little bit, even better!

Praça Cantão before it was painted. Photo Credit: Haas & Hahn.

Praça Cantão after it was painted. Photo Credit: Haas & Hahn.

GALO: On your Web site, you mention that your colors are inspired by the community. Can you expand on this process? Where do you draw inspiration for the patterns and images themselves?

H & H: Jeroen does the color research of each area we paint. The colors for the Praça Cantão and Philly Painting designs are based on the color pallet of the area, collected after a study where hundreds of pictures are made and the most common colors you’ll find in the area are collected.

We are definitely inspired by the “make something out of nothing” attitude of hip-hop culture but also by the courage to go big, which an artist such as Christo possesses. At all times, we feel that it is best not to focus on what you know, but instead to focus on what you don’t know and need to learn about a situation before you can work there. People often assume you become good at something by knowing all about it. I think we got better at what we do by realizing that one can never know how another community functions. The less baggage you bring to a new project, the easier it becomes to build a plan. We became better at basically asking everyone about everything. Not only did we learn very fast how we should organize our plans, we also built projects that are based on local thought-patterns, which means the projects themselves become local.

Vila Cruzeiro before it was painted. Photo Credit: Haas & Hahn.

GALO: In the past, how has this project been received within the neighborhoods and Rio itself? Have you experienced any backlash from people such as politicians or community members from the areas you’ve already painted?

H & H: We are fortunate that we haven’t received negative reactions.

The project created identity. There’s hardly any Facebook account in the Boy with Kite area in Vila Cruzeiro that does not show that particular image. People also remember it was painted during the time before police occupation.

All communities where we painted have been extremely supportive and proud. Many people ask us if we can continue the project and include other communities as well. As we have lived and worked within the communities, there is a very strong bond between us and the inhabitants. It was and will always be a great immersion. It was not only us who brought colors to their homes. The community people have enriched and inspired us in many ways.

The future look of Vila Cruzeiro. Photo Credit: Haas & Hahn.

GALO: What do you see as the future of this project? Do you hope to move beyond the confines of Rio? Can other slums around the world be transformed in the same way?

H & H: We have been invited to many countries, from Colombia to China, to discuss potential projects. Philly Painting was the first project we did “by invitation.” It was an initiative from the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, and a collaboration with several partners. We like to think that the project idea can be “translated” to other cities, but it’s important to realize that every place demands a different approach. It’s impossible to simply copy-paste the project, so sometimes it feels like one has to reinvent the wheel. You first have to really understand a place, its people and its culture, before even thinking about starting a project there. We believe that every place is unique. It has its own distinction and beauty.

Video Courtesy of: Favela Painting.

For more information about the project or the artists, please visit http://www.favelapainting.com.