The Caribbean: The Meeting Place of the Modern World

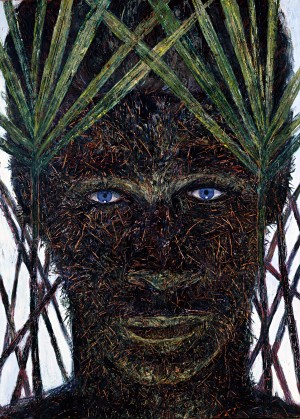

The tropical textures and impressions evoked by Rabell’s piece are a result of his fantastic imaginings of the human self, which seem authentic to the Caribbean, but distant to American ideals of beauty. Looking at the piece, it almost appears like the man came right out of a forest or jungle to escape into your human conscience; an image of dreams that, ironically enough, seems shaped by real-life matter. According to Fuentes, this is just one of the many innovative, worldly ways, in which the exhibition confronts certain subject matters like identity.

“We’ve employed a polyphonic perspective to deal with a huge archipelago that it is as diverse and complex as New York City, which is, to many, the largest Caribbean city,” Fuentes said.

Indeed, this group of islands is quite vast and complicated. The tropical region’s topographies and natural environments are breathtaking, with artists able to reimagine them in such distinct, inventive ways, like those seen in Rabell’s island man, or in one befitting piece, which is a part of the third segment of the exhibit — one that is properly entitled Fluid Motions for its focus on a coastal and geographical context, being presented currently at the Queens Museum of Art.

Mermaids frame the various Caribbean waterways, islands and coastal areas, in Rigaud Benoît’s (Haiti, 1911-1986) Mermaid oil painting. It depicts a mysterious woman with a red, intricate scaled tail; she is floating in what appears to be an animated serenity. Topless and free, the mermaid extends her brown arms with a colorful maraca in her right hand and a doll in her left, silently beckoning the sea creatures to gather round for a secret ritual.

Reminiscent of the mermaid Lasirèn, who is a part of the Voodoo tradition in Haiti, the mermaid hypnotizes both the fish and the viewer with her tail dance; the legend goes that the mermaid’s spirit can enter the follower’s body, and it is believed to bring good luck in regard to money, love, health, and work. The mystical tales of mermaids like Lasirèn were historically chronicled in African and European stories. For example, the African slaves shared their imaginative tales with the Caribbean people.

Actions like that demonstrate that the region’s waterways played host to fantastic legends; tales that could have scared off or motivated the various early explorers and traveling traders (it makes one wonder if Christopher Columbus had heard these tales before he sailed the ocean blue in the 15th and 16th centuries).

The picture incites the supernatural skeptic in you, more so than in the other retrospectives, and that in itself is ingenious. It subtly demonstrates that the high seas were areas of great movement, full of hidden wonders and quests. The mermaids have been persuasively placed right at the North entrance, so that each viewer has a chance at a little bit of fantasy before walking deeper into the realm of Fluid Motions and being confronted by more complicated realities.

Commingled ideas of race, culture, and paradise

Accompanying the Caribbean waterways’ fanciful displays at the Queens Museum of Art, there are also festive explorations of the region’s annual Carnival events, which are lively celebrations of life, folklore, culture, religion, and traditions. One depiction of these events is through a work by Emilcar “Simil” Similien (Haiti, 1944), who presents a female black silhouette (perhaps a Carnival dancer) together with a jovial inducing feeling perpetrated by an eye mask, which has red and light blue feathers sticking out of its sides. If you look further down south, the only other splashes of color are of the dark figure’s gold bangles, small streamers dangling from her shoulders, nipple tassels, and a solitary ring.

Similien’s piece is entitled Milatoni Mask, an acrylic on canvas masterpiece that is silent, yet affective. It captures the festival’s bright, theatrical feel with a gentle subtlety; even with only the pitch black figure showcased in the piece, you cannot look away. It’s a seductive masquerade, perhaps lacking a tangible human face in an effort to speak to the practice’s forbidden roots: African slaves were forced to practice singing, dancing, and other harmonious movements in secret, which are now at the heart of Carnival. Staring at the image long enough, one might assume that the figure has come to life, moving from side to side, her streamers and nipple tassels swaying seductively as the clasp of her bangles makes a faint noise while they dangle against one another; it is easy to let your imagination rip.

It is also easier to perceive the Caribbean as an area of lively beauty and emotion after looking at the artworks than that of darkness and uncertainty; and it is that same grandness and mystery that is tastefully exuded in the works at The Studio Museum in Harlem.

Smack in the middle of the mixed arts and culture community lies this artistic offering; it feels like a rebirth of the Harlem Renaissance, considering the location and the exhibit’s showcasing of definitive, culture changing artistic works — half of them explore the connections between race, and the region’s history and culture under the theme, Shades of History. Particularly emotive is Goyita by Rafael Tufiño (New York, 1922-Puerto Rico, 2008), an oil on Masonite piece. It is the central frame of a black slave with old, poignant eyes and pursed lips — searing signs of his sagacity and age, along with the struggle that marks his existence (a standout piece by far).

With Tufiño’s piece, the artist had to be making a pathos appeal to viewers; he believably conveys enslavement’s ills with an entrancing weary gesture. Perhaps the man depicted in the work was ready to migrate to America for a better life, as several Caribbean groups had done in the 1900s, or perhaps he was too tired to start over. His face shows no alarming hints of revolt, or the very angry outburst that would have had to happen on the slaves’ part, in order to incite the Haitian Revolution. However, it seems to fit in with the exhibition’s overall grand design, for the slave could be of Creole descent, or be just as easily forced to the Caribbean from a foreign land or vice versa (connecting the Caribbean slave with the world).

It is the most hard hitting thing to think about, but the difficult subject matter — perhaps the most difficult theme of the whole exhibition — is manageable (just ask some of the museum goers like I did).

Possibly a gentler entry point into the theme, are the captivating black and white gelatin silver print photographs of two Hispanic women, who emit a certain dignity while polishing and shining silverware, plates, and other sterling items; they evoke a quiet integrity with their facial expressions. Befitting of a compulsory tranquility that equally emanates from the pictures as well as of those who serve others, the women in the photos do not seem like natives, but rather immigrants (perhaps a part of the Spanish lower nobility). It is during that particular realization that the artwork inspires empathy, but just a few more steps into the surroundings would reveal something more bold and strong.

Another powerful image is of Renée Cox’s (Jamaica, 1960; presently lives and works in New York) Redcoat, a color photo from the Queen Nanny of the Maroons series. At first glance, it captivates one’s attention due largely to its colossal size – the image takes up a whole wall near the museum’s gallery entry and exit doors. Given a second look at the photograph, one notices that there is an undeniable power exuding from the fierce black female warrior, who boldly stands and commands our attention. She stares with wide eyes, her black dreads falling onto a bold red soldier’s uniform with gold trimmings, arms crossed as if to signify a readiness for battle. If that is not enough to suggest power, fear, and domination (a contrast to the earlier image), in her grasp she holds a lethal sword with steady precision in the picture’s center. And while you notice the beautiful, lush greenery and clear blue sky in the background (suggesting a nirvana), you cannot bear to take your eyes off the subject’s mesmerizing presence for fear of missing a quintessential detail of her nature and determination.

The woman in the image appears to be a Maroon, a defiant Jamaican slave; popular knowledge tells us that they were mostly West Africans and skilled fighters, who escaped and freed others from slavery, forming their own hidden communities in the region’s peaceful, verdant terrain.

Cox plays her part in bringing forth this duality theme of Land of the Outlaw — seeing the Caribbean as both a utopia and an illicit place. Under that principle, the artwork proves to showcase more than one perspective, and in turn, creates multiple arenas for discussion and contemplation, even after having left the museums’ changing worlds.

Therefore, whether a piece inspires singular, dual or ambiguous interpretations, the multi-venue exhibition stays true to forming direct and indirect connections between the Caribbean and the New World, with little mess — for the most part.

“Caribbean: Crossroads of the World” runs from now until January 6, 2013 at the El Museo del Barrio as well as the Queens Museum of Art. The exhibits runs until October 21 at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

The El Museo del Barrio is located at 1230 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10029. For more information, please visit www.elmuseo.org or call (212) 831-7272.

The Queens Museum of Art is located at the New York City Building, Flushing Meadows Corona Park, Queens, NY 11368. For more information, please visit www.queensmuseum.org or call (718) 592-9700.

The Studio Museum in Harlem is located at 144 West 125th Street, New York, NY 10027. For more information, please visit www.studiomuseum.org or call (212) 864-4500.