The ICP Triennial: A Different Kind of Disorder

Alternately beautiful, bombastic and occasionally brilliant, the International Center of Photography’s current exhibit, A Different Kind of Order: The ICP Triennial, features 28 emerging and established artists from 14 countries. Their combined works reflect not only photography’s seismic shift to a digital image-making universe, but an unquestionable and disturbing disorder in the world at large.

In executive director Mark Robbins’ words, the show “reflects our present moment of a new kind of order shaped by social, political, and technological changes.” If there is order to be found, it’s in the thematic choices of curators Kristen Lubben, Christopher Phillips, Carol Squiers and Joanna Lehan. These are defined as Aggregation, the scavenging and reorganizing of the chaotic stream of Web images; Collage, the employing of photographic fragments, digital images, paint, three-dimensional objects and audio/video material in unprecedented ways; Mapping, an attempt to find meaning out of disarray in the environment, and Community, the search for connection in light of the ubiquitous bombardment from the Internet. All of the artists shown employ one or more of these themes in their offerings.

Credit should also be given to WORKac, a New York City-based firm involved in architectural and urban planning around the world. The entire center has been reconfigured to give a generous and uncluttered amount of space and focus to the individual artist. Low, non-obtrusive benches are placed at a respectable distance from many of the larger displays — this is a welcome relief for the visitor who needs more time to contemplate the unrelenting mosaic of images that can confound and overwhelm even the most sophisticated viewer. This is especially important when confronted with the numerous video presentations available. The care taken to create a unified journey through the upper and lower floors of the exhibit is something we’ve come to expect from larger, well-endowed institutions like the Met or MoMA. In a less grandiose setting like the ICP, it is impressive to say the least.

The Artists

Aristotle declared that “the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” For many of the artists represented here, the obsession to find meaning in a disordered world is obvious. The influence of another fifth-century B.C. Greek, Euripides, plays predominantly in Elliott Hundley’s massive display, Pentheus. Based on a story of Dionysus’ revenge against his cousin, Pentheus, large inkjet images on rice paper are mounted on soundboard with overlays of small figures cut from his photographs, pieces of Euripides’ text, and hundreds of found images floating over the landscape of the piece, affixed with numerous pins. The helter-skelter placement of magnifying glasses entices the viewer into a close-up peek of these vignettes but as some are deliberately positioned out of reach, we are left with the impenetrability of the work as a whole. Wall notes make comparisons from Hieronymus Bosch to Jackson Pollock. So many images fight for our attention that it’s almost impossible to find a footing or focus. Is there a way to virtually enter and exit this labyrinthine work with an answer? It’s doubtful but this Los Angeles-based artist’s gargantuan effort is worth the attempt.

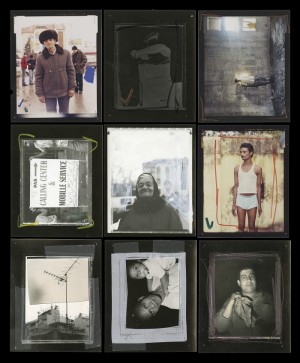

A more translatable aggregate of photo imagery can be found in the collaboration between British artist Patrick Waterhouse and South African photographer Mikhael Subotzky. This politically-charged investigation of Ponte City, an ill-fated 54-story residential tower in Johannesburg, South Africa comprises three oversized lightboxes containing photographs taken between 2008 and 2010 of every window, internal door, and television set in the tower.

The best way to approach the work is simply to let the multitude of images wash over one’s sensibilities until a few pop out indiscriminately and demand attention. Ponte City became a nightmarish symbol of post-apartheid struggles with the white race in flight from what had once been exclusively their domain. The grid arrangement of images creates a claustrophobic feel of residents trapped inside. Black youths peek from doorways or capture our attention behind partially-opened curtains. Walls are scrawled with a large “NO” or warning signs such as “Not responsible for loss by fire, theft, damage or any other cause whatsoever.”

In the midst of such an outpouring of imagery, Wangechi Mutu’s exquisitely-rendered collages of hybrid, anthropomorphic creatures are a thing of beauty, in spite of their fragmentary and disturbing nature. A woman’s breasts emerge from the end of a snake. A swirling phallus-like shape is juxtaposed with a bird’s hungry beak. With a concoction of ink, latex paint, gold glitter and a smatter of pearls on contact paper attached to linoleum panels, this Brooklyn-based artist from Nairobi, Kenya works a surrealistic magic.

The ways and means that these 21st century innovators employ are often as arresting as the works themselves. The advances in satellite technology are put to an arresting use by Mishka Henner, a Brussels artist currently working in Manchester, England. His Dutch Landscape series of geometric abstractions employ maps found on Google Earth, introduced four years after the September 11 attacks. Security concerns from various governments required Google to obscure details of certain sensitive sites. Through colorful polygons and large blob-like shapes, Henner has obscured these off-limit spots on his maps.

(Article continued on next page)