‘Through Her Eyes’: Voices of Ecuadorian Female Athletes

As an athlete growing up in Evanston, Ill., Stanton remembers believing she could do anything that she wanted to. With the logic of hard work and a “yes” attitude instilled in her by her family and the athletes she was exposed to, her experience is far from what many females are faced with in other countries around the world.

“I grew up in a world where there was a women’s Olympic basketball team. I grew up when the Chicago Bulls were really good. Seeing Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant, I wanted to be them. I didn’t think that I couldn’t be them…,” she expressed. “I feel fortunate that I grew up in [an environment] where I knew I could do anything that I wanted. I know how fortunate I am that I can’t recall a time when I didn’t think I could do something. If I worked hard enough, sweated it out enough, I believed I could get to some place. I think that not everyone has that everywhere, even here in the United States and all over the world. I think part of it comes from my family, part of it comes from the culture you grow up in, and part of it comes from portrayals in the media.”

While Stanton was in Ecuador, she said that many of the women and girls she interviewed did notice a change in the attitudes of females in sports, mainly the acceptance of women and girl players and taking their desire to be athletes seriously, but that there was still a lot of work to do. According to Stanton, negative mindsets still exist, along with the presence of very little support from many families. For that reason, there is a belief that nothing beneficial can come out of sports, physically or mentally. “There are families, mothers and fathers, teachers, others, who think sports is something that will lead their daughters to not be successful in school; that they will lose their femininity and become masculine; that it is a waste of their time; or that, as women and girls, they simply don’t belong on the field.”

Aside from this standpoint, Stanton doesn’t know the reason why there is still so little media coverage on women’s sports, but she uses this lack of exposure to create and leave a bigger dent in the minds of thousands through the growing existence of Through Her Eyes. And despite the lack of equal reportage, there are indeed females who do have moral encouragement and backing by family and friends, even with roadblocks along the way.

“When you dig to the level of the barriers that [these athletes] have crossed many times to do it, they don’t always have the support from their families, society or monetarily, “Stanton said. She later added, “I hope that by sharing these images, we can change the media landscape and the way women and girls view themselves, and the way the world views them.”

In her video, Vinueza recalled a time when society thought that girls could not surf because they were thought to be not strong enough to stand up on the surf boards. In actuality, she feels that it is less about strength and more about “fighting for the waves.” She found surfing through her brothers. Over time, she has seen the sport grow in the number of female participants. Nevertheless, there is still a disparity.

There is also a gap in the number of public and private grants awarded to women. Vinueza is fortunate enough to have received sponsorships and support from companies and organizations for sports gear and financial aid to enter competitions.

The idea behind Through Her Eyes is that even though there are many females participating in activities and sports, there are many who are not. Stanton hopes that by documenting those who are and showing their triumphs and successes, it will serve as an influence to get the girl who doesn’t think she can do it to try.

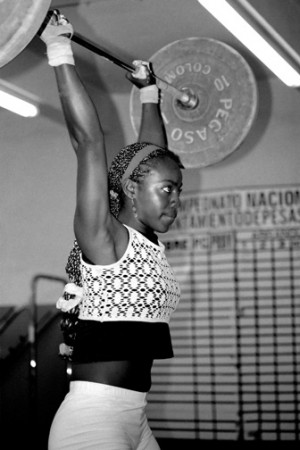

More recently, in early June 2012 on 18th Street, in a Chicago loft amongst a string of art spaces in the neighborhood of Pilsen, Stanton introduced these subjects to an American audience. The walls were filled with imagery of strength, comradery, and confidence. Females of all ages, backgrounds and sport levels, created a full and inclusive look at the voice of what many Ecuadorian girls experience, think, and feel in regards to being active.

There were photos and a video profile of an archer, Romina Quiroga, who might give Hunger Games’ Katniss Everdeen a run for her money. Collected, confident and skillfully precise, she has the stance of a huntress just before she frees the arrow from her bow. Quiroga is one of few females that represent Ecuador in this sport nationally and internationally. Notwithstanding, that does not stop her from continuous progression in her personal goals and achievements. She was national champion for eight years in a row and remains a top athlete in archery on a continued journey to win a medal for her country on the global stage.

“What I have discovered is that women who are practicing weightlifting, cycling, all of them are moving forward. Because truthfully, before we were totally at the bottom, women’s sports weren’t even known. It was almost as if women had neither a voice nor a vote. Now there has been a great deal of progress in women’s sports,” Quiroga said.

Quiroga advocates for females to not make excuses for reasons why they cannot do something, such as anything outside of what they perceive to be their domestic responsibilities, namely for lack of time. She expressed that there is always time to take care of the body and the mind.

A similar expression was evident throughout much of the rest of the exhibit shown in Chicago. The intensity of devotion and the satisfaction that the women athletes get from something they have a passion for, transcended throughout the photographs and video accounts. The photographs were real and vivid, while the video footage complimented them, giving the subjects more life and significance. Shown were all-female teams bonding together as a collective during a soccer match in live-action across a field as well as two young girls in their purple leotards practicing pirouette type movement in a gymnastics exercise at their community gym. No less vibrant was the color photo of a woman runner with corn-rowed hair and sun kissed skin in a deep concentrative zone on the track in the midst of a race.

Stanton expressed that she wanted the exhibit to be a mixture of powerful images, with close-up shots where you could see the athletes’ facial expressions or their muscles, and also ones more panoramic to show where these participants live and play.

“Of course women are playing sports,” Stanton said. “That’s what I wanted to go around and capture. There are also tons of women and girls who aren’t playing sports because they don’t have the courage or the time, or the ability to go out there and do it. The idea is that when sharing these visuals, someone will see it and say, ‘Wow, that girl is just like me and her dad told her she couldn’t play either. But she kept doing it and look at where she is now.’”

Sharing the stories of these women and girls by creating a space online and in galleries – a live space that is not necessarily prevalent or present at this point — is what Stanton articulated to be what this project is all about. She hopes to create an expansive network of athletes to interconnect females from all across the globe. Stanton fervently believes in the power of sports and its ability to change and be a catalyst for personal growth and accomplishment.

In many situations, according to Stanton, the choice and goal does not even have to be focused on organized sports or games. The decision to take a leap and be active in any way speaks just as loudly and soundly as victory over a winning soccer goal or crossing over the finish line. Though only featured briefly in Through Her Eyes, Stanton came across a woman, while in Ecuador, and found her to be an inspiration, after she heard her tell her personal story of walls being broken down – the woman was Rosa Elena Moreta.

Moreta was one of the first indigenous women to summit Cotopaxi in the Andes mountainous region of Ecuador. When she reached the glaciered mountaintop, one of which climbers from around the world come to scale, she put on her native garb of a dark skirt and a white top, with colorful embroidery at the neckline, with the feeling that she could take on the world.

Moreta decided to try to conquer Cotopaxi only after receiving encouragement from a Peace Corps volunteer named Dana, who came to work in her community alongside the mountain. Reluctant to join Dana at first, Moreta and another indigenous woman also from the area, Maria Isabel Juma, ceded and made the ultimate journey together. Yet, even after this accomplishment, her community questioned her actions on why she bothered to do such a thing. However, after living underneath this natural wonder for so long, something became clear to Moreta and changed her outlook on how to approach living life. She realized that those four walls of her house did not need to limit her anymore. She could go out into the world and do things for her own personal growth, and still be there for her family. As a result, she became more active in her community and was recognized for her capability to lead. Moreta is now considered to be the first female elected in her community to a leadership position.

To learn more about the traveling exhibit or to follow its ongoing progress, visit one of the following sites: http://throughhereyes.org or http://throughhereyesproject.tumblr.com/.