“Blue Nights” Addresses Loss During the Twilight of a Life

“In certain latitudes there comes a span of time approaching and following the summer solstice, some weeks in all, when the twilights turn long and blue.” So begins Joan Didion’s memoir Blue Nights, the 188 page metaphor, comparing the waning of life to the blue twilights at the end of a summer day.

The novel reads as an extension of Didion’s openhearted international bestseller, The Year of Magical Thinking, a memoir about the loss of her husband, John Gregory Dunne (who died of a heart attack at the dinner table), which Didion completed within 88 days after his death. During this period, Didion’s adoptive daughter, Quintana Roo, was in and out of hospitals with severe complications from pneumonia. Quintana eventually passed away within 20 months of her father’s death. She was only 39.

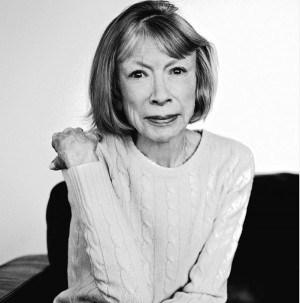

While Blue Nights recounts much of Didion’s experience of losing her only daughter, the book focuses extensively on her depression over growing older and the loss of those around her. Less descriptive of the procedures and complications Quintana endured during her elongated hospital stays that surfaced in her predecessor, Blue Nights focuses predominantly on the 76-year-old author’s anguish and suffering.

“This will not be a story in which the death of the husband or wife becomes what amounts to the credit sequence for a new life…” she explains in The Year of Magical Thinking, and her newest work seems to labor through that same idea. This memoir is an honest account of her grief. Eight years after Quintana’s death, the lanky, five two, frail writer is still in mourning.

She does not attempt to show the brighter side of the situation, nor does she rejoice in her memories of the deceased. When she looks to the past, Didion instead tries to understand her daughter’s thoughts, actions, and words. Quintana had been diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder, and the Upper East Side resident recounts her daughter’s mood swings and death wishes that had taken their exhaustive toll on her.

Though raw and sincere, Didion’s writing style is at times repetitive and explanatory with some passages reminiscent of a self-help book rather than that of a memoir, consequently failing to evoke as much emotion as personal anecdotes might. Instead of bringing her readers into family experiences, Didion often repeats Quintana’s expressions or her own ideas. “When someone dies, don’t dwell on it,” Didion rehashes her daughter’s words throughout the work in a ghost-like manner, relentlessly struggling to follow her advice.

However, despite the discrepancies in a novel that was almost scrapped by the writer herself, her narration can be seen as philosophical and mind-bending as she delves into the subject matters of love, parenthood’s hardships, and aging in a world where technology has overtaken human interaction. “When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children,” is a phrase that chimes throughout the memoir, showcasing her existential inclinations, as she periodically insists that a parent’s greatest fear is losing a child. The entire volume is an unconventional manifestation of this.

In addition, the novel offers a sense of vulnerability; an exposure of human guilt and compassion brought on by her personal questioning of her role as a mother. Was she good enough? Could she have done anything differently? But her questions remain unanswered as she journeys through the past, insinuating between the written lines that adoptive parents never cease wondering if they can fill the shoes of those who left their child behind.

(Article continued on next page)