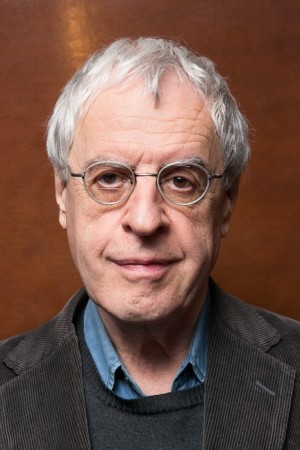

Charles Simic: A Man Who Does the Impossible

GALO: So you do not have a Facebook account?

CS: No, it’s a kind of narcissism. You also have to remember where I come from; I grew up under communism and the Nazis, and the notion of an institution like that [is not for me] — any spy agency would be delighted to have that information!

GALO: Yes, telling them everything!

CS: Not too many enthusiasts with our history! [Laughs] Again, it would be too time consuming! I have better ways of spending my time.

GALO: Many of your experiences have been shaped by interactions with Gypsies. Do you feel that the Roma have been relegated and kept to the status of “the other” throughout Europe? Last year in France, for example, thousands of Roma were expelled by Sarkozy’s government. Although Sarkozy was ousted in the recent elections, it does not seem like the change in regime will change very much for the Roma populations. Today in Europe, many affluent Roma do not even admit to who they are. What effect do you think this has in Europe and how had your experiences with this group, which has always been relegated as “the other,” changed your outlook, your writing, or your beliefs? I know you were treated as a “displaced person” in Paris yourself.

CS: It’s disgusting. It’s a convenient thing to hate the Gypsies. In Hungary, for example, where there is a right wing government, you’ve got to hate the Gypsies; you’ve got to hate the Jews. Czechs have been treating them very badly (the Roma), and other places too. The world is a funny place. Things get better. Then the moment there are economic difficulties, there is a need for scapegoats, there is a need to distract the populace. Conveniently, there are always the Roma, or the immigrants, or whoever it is. What is horrible is that I thought France would be a more enlightened place. It was purely for political reasons. Sarkozy wanted to get Rightist votes.

GALO: About one in 33 adults in the US right now are under supervision of correctional authorities. PEN’s Prison Writing program attempts to give prisoners, who might not otherwise have a voice, a chance to write and be heard. As someone who’s father was jailed several times, did you feel yourself drawn to PEN and its work for that reason, and do you see a restorative power in writing about trauma in general?

CS: Trauma, I don’t like that word. The world is always what it is. It’s always traumatic. There’s nothing new about it. I grew up during the war. Since then, I’ve seen so many wars. My brother was in Vietnam. My son almost went to the first Gulf War. It’s endless. It just goes on. It’s not that I was writing about these things especially. It’s something that’s always around me. I write about that.

GALO: That goes into my next question. You’ve talked about a split you experienced as a child were in school you were told Tito, Stalin, and Lenin were great men, and at home, you were told they were terrible men. Had that division of truths, early experiences with propaganda, and the major role of politics in the home, confused you as a child or made you see more than others might?

CS: I don’t think I was ever confused. At home is the primary influence. I’m sure there were kids who were older, teenagers and so forth that would have been swayed by what they heard in school and those awful things in communist countries where teenage kids would denounce their parents for saying nasty things about Stalin or whoever. It’s very difficult for me now to understand. I chose to believe what I heard at home to what I heard in school. There was never some kind of a struggle.

GALO: The authority rested in the home.

CS: Yes.

GALO: You grew up in Belgrade, lived in Paris, New York, Chicago. What do you like to identify yourself as? Do you say to yourself, “I am a New Yorker,” or do you see yourself as the sum parts of all these cities?

CS: I’ve divided my life pretty much between New York and New Hampshire. I lived in NH since 1973. I lived in NY on and off…Jesus…since 1954! New York is the place I feel most at home at and New Hampshire after that.

GALO: You write in English and you’ve previously said that the Serbs do not see you as one of their own writers. Despite the imposed exile, do you see yourself as a Serb writer or does writing by definition cross boundaries and borders for you?

CS: I’m not a Serb writer. I lived there in my childhood. Serbs will tell you that I’m not a Serb writer; I’m not a Serb poet. I’ve never had anybody in Serbia say that “he’s our writer.” He’s not, you know? [Laughs] I’ve lived most of my life in the United States, so inevitably I write in English, and I write about the United States.

GALO: A bit of a morbid question, but you had once said your earliest childhood memory was a bomb blast next door which knocked you unconscious and brought your mother rushing in. What would you like some of your last memories to be?

CS: It was my earliest memory. That’s the first thing I distinctly remember. I was a few years old. They are not consecutive memories, but broken up memories of what ensued in the days after that. Last memories? I’ll have to think about that!

GALO: In addition to being a fashion designer, is your wife, Helen Dubin, also a storyteller? The lines, “each tree on my street had its own Scheherazade,” in one of your poems, really stood out to me. I’d wondered if you’d married your very own Scheherazade.

CS: Not quite, no — a lot of things in poems are things that I’ve made up. She was not in that poem.

GALO: Does your wife read your work and comment?

CS: Yes, she does. She’s a good critic.

GALO: Have you ever changed anything due to her advice?

CS: Yes, sure! She’ll say, “This poem stinks,” and I have to agree.

GALO: Last question! Who are you reading right now?

CS: I read a lot of different things. [Laughs] Just before you called, I was reading Hemingway’s short stories, rereading old Hemingway stories, the story of his called The Killers. I read all the time. I’m one of those people who is constantly reading.

GALO: Would that be your advice to youth today? To read, read, read?

CS: I think all writers, poets, intellectuals are big readers. You can’t be any of those things without reading a lot. If you want to be a musician, listen to a lot of music and whatever kind of music you are interested [in]. That’s the advice I usually give. It is inevitable. You have to accustom yourself to that world which that particular artist created. Get to know it’s traditions, it’s nuances, and so forth. So, yup!

GALO: Thank you so much for your time!

This interview was conducted by GALO Magazine’s writer Mariya Yefremova a few weeks after the PEN World Voices Festival in May 2012.