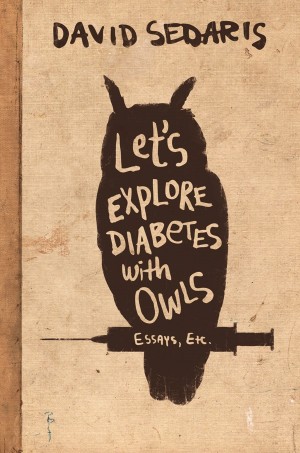

David Sedaris’ ‘Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls’ Is Hilarity Punctuated by Stirring Honesty

Without the inevitable march through banality and absurdity, life’s most valuable moments wouldn’t make much sense. Nor would they be as easy to savor. Elementary school swim meets and childhood songs about kookaburras don’t mean a whole lot on their own, but they suddenly encompass everything when they underpin stories about a father’s callousness or the meaning of family. David Sedaris’ new book, Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls: Essays, Etc., is a hilarious, wrenching journey through a life of bizarre experiences, fleeting moments of hatred and surging undercurrents of love.

The book is brisk and addictive, thanks to Sedaris’ ability to jump from levity to gravity — and back again — in a matter of sentences. Some chapters are funny and light throughout. For example, “Attaboy” is an excruciatingly awkward story about Sedaris’ father wrongly accusing a neighbor boy of calling his wife a bitch, and upon acquitting him, giving him as much putrid, off-color ice cream as he wants. It redresses two extremes of parenting — the contemporary notion that children are only to be coddled and sheltered, and the antiquated methods of corporal punishment and perpetual indictment. But Sedaris does this by hilariously making the case for both, and the whole chapter maintains an atmosphere of incredulous buoyancy. However, Sedaris seems most at home recounting stories with elements of tragedy, farce, disappointment and triumph beautifully sewn together in a colorful weave.

One of the most arresting sequences is contained in the chapter titled “Memory Laps,” which takes place at the Raleigh Country Club in 1967. A young Sedaris secures a place on the swim team, but he isn’t desperately excited about it, “This sounds like an accomplishment, but I believe that in 1967 anyone could be on the Raleigh Country Club team.” As Sedaris’ father interminably heaps praise on one of the other swimmers, a boy named Greg Sakas, Sedaris handles his frustration by insulting his sister and focusing on Greg’s less enviable attributes, among other crude methods.

“I was being forced to hate him, or, rather, forced to hate myself for not being him,” Sedaris remembers, “It’s not as if the two of us were all that different, really: same size, similar build. Greg wasn’t exceptional-looking. He was certainly no scholar. I was starting to see that he wasn’t all that great a swimmer either. Fast enough, sure, but far too choppy.”

Reading Sedaris as he ventriloquizes his 11-year-old self is one of the great joys of the book. All the petulance and innocence of a child is channeled through the indignant eyes of a grown man, and the effect is oddly natural. The triviality of childhood is always tempered with the tensions and joys that attend the process of growing up. It’s also relentlessly funny. However, the chapter ends with a heartbreaking meditation on the nature of Sedaris’ bruised relationship with his father.

When the young Sedaris finally beats Greg Sakas in the butterfly, his father seems upset about it, “Besides, that was, what — one time out of fifty? I don’t really see that you’ve got anything to brag about.” Upon hearing about his son making the New York Times bestseller list 41 years later, he merely scoffs, “Well, it’s not number one on the Wall Street Journal list.” Sedaris frequently returns to his father’s cruelty, unafraid of confronting it and more than willing to draw from it. Although many of these anecdotes are saturated with humor and sarcasm, the denial of a father’s love is a wound that can’t be erased with cleverness. “Memory Laps” closes with honesty and weight.

“The crummy part of swimming is that while you’re doing it you can’t really see much: the bottom of the pool, certainly, a smudged and fleeting bit of the outside world as you turn your head to breathe. But you can’t pick things out – a man’s face, for example, watching from the sidelines when, for the first time in your life, you pull ahead and win.”

Most of the book is written from Sedaris’ first-person perspective, but he occasionally assumes other personas who spout monologues about everything from a Jesus dictatorship to an atrocious woman’s petty grudges against her paraplegic sister. The former is a chapter titled “If I Ruled the World,” and it’s one of the weakest portions of the book. Sedaris is at his best when meandering through the real world, filtering it through his uncanny understanding of and appreciation for reality. Thus, it makes sense that he never really finds his footing when ranting from the mind of a fictional, would-be Christian autocrat. The character says, “I’ll crucify the Democrats, the Communists, and a good 97 percent of the college students.” Yes, there are unpleasant people who’d like to impose their religion on the rest of us, but the chapter is uncomfortably hyperbolic. Sedaris usually ridicules and embraces realities that others only subconsciously notice, if at all; so a chapter without a hint of reality doesn’t work.

The chapter titled, “I Break for Traditional Marriage” is equally ill-fitting. In it, a man abandons his moral sensibilities after gay marriage is legalized in New York. He then makes a list of all the socially unacceptable things he’d like to do — like brutally murdering a few of his family members. Sedaris is a gifted caricaturist because he recognizes idiosyncrasies in all their subtlety and humanity. His metaphors are often as telling as they are funny. For example, his description of a downtrodden, drunk gambler dubbed “Johnny Ryan” is remarkably palpable, “Once he hit thirty, a hardness would likely settle about his mouth and eyes, but as it was – at twenty-nine – he was right on the edge, a screw-top bottle of wine the day before it turns to vinegar.” Unfortunately, his peculiar eye for reality is conspicuously absent from the aforementioned chapters, which coldly revolve around psychopathy instead of everyday humanity.

Thankfully, for every moment of disillusionment, there are 100 moments of brilliance.

Almost every disparate thread of the book is strung into a 13-page essay called “Laugh, Kookaburra,” which first appeared in The New Yorker in 2009. During a visit to Australia, Sedaris and his partner, Hugh, have a conversation with a woman named Pat. Pat informs them that they can only be successful if they cut off one of life’s four “burners” — family, friends, health or work — and that they can be really successful if they cut off two. Pat switched off her family and health, Sedaris cut off his friends and health, and Hugh cut off only work. Apparently, he’s content with moderate success. Sedaris says Pat “seems like a genuinely happy person. And that alone constitutes success.”

After the three of them make their way across a patch of Australian countryside (the “bush,” as it’s called down under), they enter a town called Daylesford — “If Dodge City had been founded and maintained by homosexuals, this is what it might have looked like.” They decide to eat at a lakeside restaurant attached to a hotel, a scene elegantly captured on the page, “The view was of a wooden deck and, immediately beyond it, a small lake. On a sunny day, it was probably blinding, but the winter sky was like brushed aluminum. The water beneath it had the same dull sheen, and its surface reflected nothing.” Sedaris ends up on the deck, feeding a kookaburra which had taken to landing on his arm. Every time he’d give the kookaburra a strip of meat, it would beat it against the deck, thinking it was still alive — “whap, whap, whap.”

This stirs the memory of a night spent singing “Kookaburra” with his sister, Amy, when she was in first grade. Upon hearing them, their father bursts into the room and orders them to bed. Sedaris recedes to his room in the basement only to sneak back up a few minutes later. When their father returns, this time irate, Sedaris reluctantly slinks off to his room again. However, “Ten minutes later, I was back. Amy cleared a space for me, and we picked up where we had left off. ‘Laugh, Kookaburra! Laugh, Kookaburra! Gay your life must be.’” Mr. Sedaris charges through the door a third and final time, now vicious. “All right, you, let’s get this over with,” he says before beating his son with an old fraternity paddle — “whap, whap, whap.”

But the bitterness would eventually drift away. For Sedaris, although it would often go dim, the family burner would remain lit, “Cut off your family, and how would you know who you are? Cut them off in order to gain success, and how could that success be measured? What would it possibly mean?”

Contained in this essay are all of the components that make Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls such a lively, affecting book. It’s hilarious, then it’s jarring, then it’s staggeringly beautiful. If you pick up a copy, you’ll read about smoking weed and getting drunk in an Amtrak “dressing room,” the queer narratives to be found in language tapes, garbage strewn across the English countryside, taxidermy, handing out condoms at book-signings, feeding raw hamburger to sea turtles (“loggerheads”), the accuracy of American stereotypes, the inaccuracy of American stereotypes, and eating sea horses. Then you’ll read about the colonoscopy that brought Sedaris and his father together for one, transient moment — or the visceral allure of a pretty Lebanese boy named Bashir. Moments of transcendence and confirmation don’t come around often, and when they do, there’s no telling what the catalyst will be.