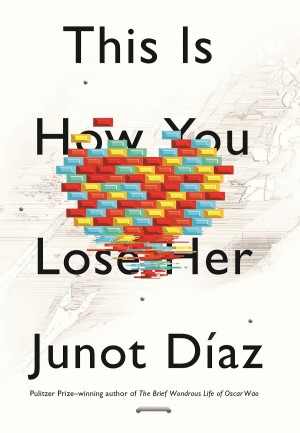

Junot Diaz: Lost Loves and Found Lives

“I’m not a bad guy… I’m like everybody else: weak, full of mistakes, but basically good.” That’s Yunior speaking, the hardheaded young Dominican-born protagonist of Junot Diaz’s new book of short stories, This Is How You Lose Her. The good news is that Diaz is not like everybody else. Human, yes; fallible, yes (aren’t we all); but as a writer, he’s a one-of-a-kind wizard of the written word — the creator of a kind of Junotspeak you will not soon forget.

Readers that were mesmerized by the tragicomic travails of Oscar in his free-wheeling, Pulitzer Prize-winning novel from 2007, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and with Junior in his earlier short-story collection, Drown from 1996, will be happy to see his reappearance in the new collection.

This is How You Lose Her is his first book in five years. It’s not as ferocious as the novel, with its descriptions of the Trujillo dictatorship years, nor is it as dead-ass funny as the ever-expanding diaspora-tinted universe in that same book. But it does manage to zigzag back and forth in its telling between New Jersey and Santo Domingo, even when the latter is a land only remembered; a land that still clings to the skin and won’t wash off. There’s also enough Junotspeak to satisfy — it’s a street-savvy, speeded up, part English, part Spanish, hip-hop lingo that Diaz owns. It’s a collection that manages to enthrall us with a young man’s doomed exploits with a lapidary precision and economy. And it’s a feat to make the ghosts of Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Carver jealous.

On Yunior’s road to true love, there’s enough boulders to build Kilimanjaro, or at the least, a sizable foothill. In “The Sun, The Moon, The Stars” there’s Magda, “a Bergenline original: short with a big mouth and big hips and dark hair you could lose a hand in.” Only problem is Yunior has cheated on her. Next thing he knows, one of her girlfriends from the Woodbridge Mall “treats me like I ate somebody’s favorite kid.” Cheating is a recurrent theme for the Dominican male. Paraphrasing Descartes, “I f—k, therefore, I am.”

He’s a poet too, this Yunior-Diaz narrator, evoking a lyricism that seeps out when you least expect it. “If this was another kind of story, I’d tell you about the sea. What it looks like after it’s been forced into the sky through a blowhole. How when I’m driving in from the airport and see it like this, like shredded silver, I know I’m back for real.” But that’s not the tale he has to tell.

The story he has to tell is a trajectory of love — Nilda, Alma, Flaca, Miss Lora — the list goes on. These tales are the upside-down, inside-out travails of lives that touch his own, lives that can bring a rough laughter to the reader but teeter-totter toward tears that don’t always come. For Diaz, it’s a dry-eyed, down and dirty world where four-letter words are the dictionary of choice.

Nilda is his brother’s girlfriend, the girl that the older brother Rafa will sneak down to the basement bedroom so their Mom won’t find out. In a Diaz story, sex — as every bit in-your-face as a Henry Miller riff — is just an overlay. These orgasmic goings-on end as abruptly as they began. Rafa may perform like a teenaged Rubirosa with his women (that ’50s-style Dominican super-endowed lover of the likes of Doris Duke and Zsa Zsa Gabor) but he’s sick, cancer-sick. We can’t help but feel that sex for Rafa is the only way he knows to ward off the grim reaper. Life and death comingle in a Diaz cosmos and sometimes personal liberation can come as a result.

In the Brief Wondrous Life novel, Oscar’s mother forces his 12-year-old sister to feel the cancerous knot beneath her breast. The girl finds this discovery a premonition; that something in her own life is about to change. “You become lightheaded and you can feel a throbbing in your blood, a beat, a rhythm, a drum. Bright lights zoom through you like photon torpedoes, like comets…it is exhilarating.” This kind of epiphany gushes forth at the reader like a breaking dam, a non-stop monologue, without brakes, that stuns the sensibilities. In these kinds of cascading descriptions lay the writer’s greatness. In This Is How You Lose Her, he has kept a tighter rein, a more mature control that doesn’t lessen his power, but makes us wish for another big novel.

Yunior’s list of conquests continue: “You, Yunior, have a girlfriend named Alma…who has an ass that could drag the moon out of orbit.” Diaz slips into a less immediate second-person voice in this tale, a frequent habit that may be disconcerting for a reader who expects the convention of one voice throughout, but this is not a writer who makes apologies. His descriptions hardly suffer in the process. After all, Diaz has a journalist’s eye for detail and he knows how to make his characters dance words around the subject or use no words at all to reveal the truth.

Nevertheless, with such a strong voice as Yunior’s running throughout these tales, it seems odd that in “Otravida, Otravez,” the choice was made to include a story about a laundress in a New Jersey hospital. It interrupts the continuity of a collection where most readers will follow our male protagonist from front to back in the book. Still, the story stands on solid ground. Yasmin’s a rock for her younger employees. She holds firm to a lover who has a wife back in Santo Domingo, and once again, the weight of hopelessness and betrayal is the name of the game.

There are many forms of betrayal and Diaz understands the uprooted Dominican woman’s pain. In “The Pura Principle,” the dying Rafa takes up with a fresh-off-the-boat Dominican whose mother had married her off at 13 to a stingy 50-year-old, before she escaped. Yunior’s mother will lament how often that happens in the campo, how she herself had to fight to keep her own mother from trading her for a pair of goats.

Yunior’s maturity in the face of changing partners seems to move at a snail’s pace. He takes up at one point with “white trash from outside of Paterson.” She’s a flaca, or skeleton, whose left eye drifts when she’s upset. Can it work? He tells her maybe 5,000 years ago they were together, when half of him was in Africa. Race is still the Great Divide. (Race is a four-letter-word in Diaz’s world, like a fuku, or a curse a Dominican never sheds.) When he takes up with Lora, an older school teacher, he fears he will never be able to be the same with girls his own age again.

Yunior’s is basically a coming-of-age story. If we were not seeing his life unfold through a lens as polished and clear as Diaz’s own, we might find ourselves as readers growing exhausted with the endless love trials of a young man who seems to refuse to grow up.

Perhaps what is most touching is the wide-eyed perspective of a very young Yunior, whose Papi has been absent for the first five years of his life. In “Invierno,” Diaz remembers the pain with the immediacy of a child, and here again his lens is unclouded. The man’s not only a stranger but a harsh disciplinarian, who puts them down in front of an unintelligible TV and refuses to let them leave. It’s the dead of winter and if he catches them at the window, it’s a slap or worse — kneeling, for example, on the cutting side of a coconut grater.

By the last story in the collection, “The Cheater’s Guide to Love,” Yunior is grown-up — in a manner of speaking — he lives in Boston, he’s a teacher of fiction, and he even has a fiancée. He’s still keeping a journal in preparation for the writer he will become and, no surprise to the reader, she finds it. She’s a “bad-ass salcedena” and the one thing she swore she would never forgive was cheating. She is the love of his life and this time it matters: “It’s like someone drove a plane into your soul. Like someone threw two planes into your soul.”

The structure of this story maps the post-breakup evolution of Yunior’s life through a series of years, a laundry list of work and play and all the predictable daily perils of existence we might expect of him. It’s a journey we trust, in no small part because it parallels so closely Diaz’s own personal history. He was born in Santo Domingo. He understands the otherness of the uprooted. He’s a professor at MIT and knows the hard punch of prejudice that Boston can deliver.

Yunior’s is a kind of half-life at best. Is he happy? Diaz won’t say. He has written about love and loss. If that is not enough, reader, then you will look elsewhere.

What he has given us is life lived. And that’s a start.