Director Bryan Coyne on His New Film ‘Infernal’ and Why Found Footage Isn’t a Genre

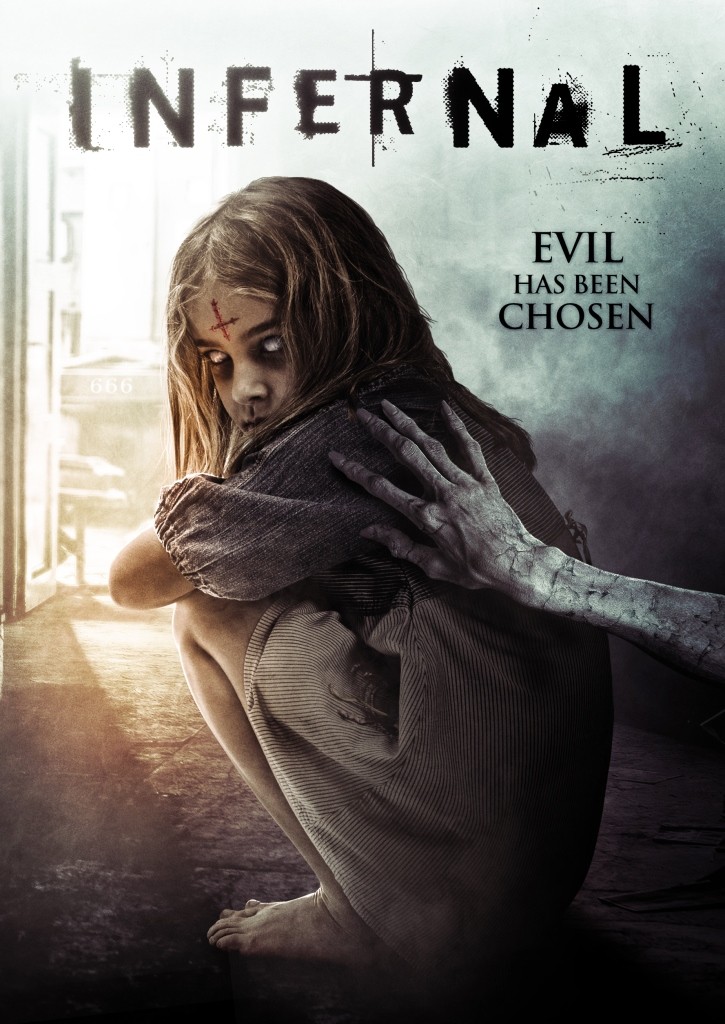

Movie poster for “Infernal.” Photo Credit: “Infernal.”

From a young age, Bryan Coyne had a foot firmly entrenched in the entertainment world. The writer-director-producer of the upcoming indie-horror flick Infernal calls his hometown of Simi Valley, California “the literal gate to Hollywood,” a Los Angeles suburb teeming with all sorts of industry crew members oiling a well-greased movie machine. His next-door neighbor, an assistant for one of the producers on the sitcom Growing Pains, would give him tours of the sets for shows in the ABC network’s TGIF lineup — think Boy Meets World, Full House and Family Matters. It wasn’t just exposure to TV and film, though — Coyne’s father was a bebop guitar player trained by jazz virtuoso Joe Pass.

Perhaps it’s not a surprise that the garrulous West Coast native — Coyne himself admits he needs Oscar fade-out music in his life — settled into a career in entertainment. But his path to success hasn’t been what you’d call traditional. Coyne earned his first directing credit as a 23-year-old on a studio project — a television documentary about baseball titled Harvard Park, which debuted on BET in 2012 and is slated for a run this year on the MLB Network. As Coyne tells it, he ended up “learning the hell of studio filmmaking before learning the hell of independent filmmaking,” a rare sequence in a modern-day industry where new directors tend to make their splash on the indie circuit. And although he calls the experience of making Harvard Park “soul-defeating,” the director says an emotional breakdown in post-production was his best experience of the whole project. “If you get up the next day and do it again, then you’re on the right track. You should be making movies,” he relates to me, speaking with the assured conviction of a philosopher.

Coyne followed-up the documentary with a producing credit on The Human Race (2013) and his newest brainchild, Infernal, both of which fall into the horror category (as does his next project, titled Utero, a body-horror extravaganza à la David Cronenberg). Infernal, which hits select theaters and video-on-demand (VOD) April 10, tells the story of a family — Nathan (Andy Ostroff), Sophia (Heather Adair) and their young daughter Imogene (Alyssa Koerner) — gradually wedged apart by a demon haunting their domestic sphere like a sinister, otherworldly squatter, and is shot and edited in a manner recalling such breakout hits as Paranormal Activity and Blair Witch Project. GALO caught up with Coyne recently to discuss Infernal‘s unique spot within the horror canon, his opinion of found footage, and the three elements essential to each of his movies.

Editorial note: Portions of this interview have been edited and shortened.

GALO: Your new feature Infernal had a very home-video aesthetic to it, in the same vein as other cult indie-horror movies like Paranormal Activity (2007) and The Blair Witch Project (1999). The cinematography relies a lot on handheld camera to tell Nate, Sophia and Imogene’s story of dread and domesticity. Why’d you decide to shoot it this way?

Bryan Coyne: There are just some things you don’t know unless you’re making the movie. Was there a lot of handheld? Yeah. But do you know how much of that film was lopped off? There were so many straight-up tripod shots in the movie.

GALO: Yeah?

BC: I have a very strange relationship within my mind and heart with “found footage.” What I like and what I loved about doing Infernal, and what I hope gets across to people, is I’m not trying to pull a Blair Witch. I’m not trying to pull a Paranormal Activity. I’m not trying to tell you this is real. That’s kind of like the jam for found footage. A lot of people are like, “in 1997, this shit happened.” No, it didn’t. Found footage is a method, it’s not a genre and people treat it like a genre. I’m saying, “This didn’t happen.” I’m not trying to pull the wool over your eyes. I love the Paranormal movies. I love Blair Witch Project. But I always tell people I feel like Infernal is more of a mockumentary, where it doesn’t have the framing devices of interviews.

One of my favorite films of all time is Man Bites Dog (1992). In that film, there’s a serial killer going around killing people and there’s a film crew following them. Here I just subtracted the film crew for the family [and them] trying to figure out what’s going on with their daughter. There’s far more familial fighting [in Infernal] than anything else in the film, the parents viciously arguing in front of a child. I was in the worst relationship of my life at the time [I made the film]. I was engaged to this young lady. I was a guy that’s always wanted to be a father. I just have that in me, and when you’re in a relationship that long, sometimes you lose track — and even if your friends are warning you that this is terrible, you’re not going to listen.

GALO: So the film is quite personal on that level?

BC: I’ll tell you that at least the next three films of mine are completely cutting the chest open, ripping the heart out and kicking it around the room. I shot Infernal in summer 2013. We sold it that October. I noodled with it for so long: I reshot the opening, reshot the ending; the girl I was with, the relationship I’m mentioning, she left me, took my cats, took some money from me, and went and married a woman in Reno. It’s such a good story [laughs]. But it was a really personal film.

GALO: Your next film, Utero, which stars the Canadian scream queen Jessica Cameron, is currently in post-production?

BC: We’re prepping to sell Utero. I’m still noodling, doing the old Bryan Coyne on it. I only do that — the noodle process — when I’m in control. If I’m going to work for someone, like with Harvard Park, I would never dare because that’s a lot of money on the line.

GALO: So Utero is independently financed as well?

BC: The original investor on Infernal, we formed a company and we just financed the next one, [Utero], too. But the next picture, we’re kind of changing our model a little bit with how we finance, because it’s a little more money, and with a little more money comes more security. Utero will go out for sale, whereas we’re probably going to pre-sell the next one.

GALO: You mentioned how you think Infernal is different from Paranormal Activity, but did it serve as an inspiration to you?

BC: Kind of, but not really. When I was originally talking about making this movie, it was like The Omen meets Paranormal Activity. And at the time, certain movies hadn’t come out that were like that. But then I’d be like, “Meet Kramer vs. Kramer (1979).” I prefer with my horror, with my terror, I like the human aspect and the reality of irresponsibility, which is really what the film’s about. If you’re not going to raise your kid right, something else will. That’s the movie, in a nutshell.

Filmmaker Bryan Coyne. Photo Credit: Bryan Coyne.

GALO: In my observation, it’s easy to be formulaic with horror films, more so than in other genres. How’d you seek to differentiate your film from others in the genre?

BC: I think we really care more about getting to know the characters. There’s not much by way of violence in the movie. I’m a pretty misanthropic guy who has gripes of life, but something I like about life is you can basically, in my humble opinion, break it down to three genres: drama, comedy and horror. And so that’s why I try to put every one of those things in what I do.

In recent years, there are so few horror films that are doing anything challenging. I thought American Mary (2012) was incredibly challenging. And something I get shit on all the time for, I thought Tusk (2014) was challenging. That argument kind of ends with, “That movie sucked,” and I say, “Did you just watch a movie about a dude being turned into [a] walrus? So don’t tell me there’s nothing interesting out there anymore.” With Infernal, though, people talk about this possession business. I don’t know what movie they’re watching. She’s [the little girl, Imogene] not possessed; she’s guided. There’s something in her life. If you’re a parent and you’re not ready to be a parent, often you’ll overlook certain things and something else will raise your child. That’s what that is.

Also, in a found-footage movie, you very rarely ever see anything. Some force is just going to toss someone because it gets pissed at something. I show you everything; everything gets shown through the course of the film. And that was a little different. You have a demon you get to see at some point. You have a certain thing that happens in the third act that you get to see. Horror is one of my favorite genres. It’s very limiting, and you’d imagine it’d be the most unlimiting genre.

GALO: Your first directing credit, Harvard Park, was on the documentary side, telling the story of a baseball field in South Central Los Angeles where eventual big-name stars like Darryl Strawberry and Eric Davis used to play ball as kids. Why the shift in genre?

BC: If you look at my [resume], you have the autism angle of Infernal [Imogene’s parents think her strange behavior derives from autism]. In Harvard, the main thing was racism. Utero is really a relationship thing, and the picture we’re prepping now is about a guy coming to terms with being a better guy, with some genre elements. I love everything. I love all forms of storytelling. I’m so into horror; I like it very much. But I’d love to have a career where I can…like Jonathan Demme, where the guy can make great documentaries and he can do the Manchurian Candidate (2004), Silence of the Lambs (1991), on and on. [Martin] Scorsese, same thing — it’s all about the story; it’s all about what strikes you.

When I make a horror movie — and it takes a year, two years — it’s not like I have to completely concentrate on that, but at the same time, part of me has to completely concentrate on that. And where’s that story you want to tell about racism in sports again? I didn’t say everything I wanted to say. I would love to revisit Harvard; I would love to revisit the concepts of Harvard.

Let’s see how many of your readers can read through the lines here — I wrote a biopic last year about a soul singer who just recently passed away. That thing is a passion piece of mine. It’s probably the best thing I’ve written, and it’s a fuckin’ music film.