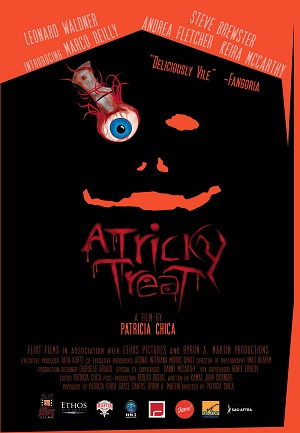

Director Patricia Chica Discusses Her Cannes Entry ‘A Tricky Treat’ and the Message Behind Killer Pumpkins

Filmmaker Patricia Chica. Photo: © John Cox.

The concept underlying the short film A Tricky Treat is a relatively simple one: what if pumpkins harvested humans to adorn their houses on Halloween, rather than the reverse? Sure, it sounds like something straight out of a bad acid trip, or something a group of stoners might mumble giddily to one another while chowing down on a pile of holiday candy. But the three-minute horror-comedy, making its debut this year at the Cannes Film Festival’s “Short Film Corner” — the festival’s market for shorts, consisting of approximately 2,000 entries — is a poignant examination of established cultural traditions.

Patricia Chica, director and editor of A Tricky Treat, is no stranger to the revered festival in Cannes, which runs May 13-24. This is the filmmaker’s third straight year with a short film entry in the French fest, having submitted Serpent’s Lullaby last year and Ceramic Tango in 2013. Serpent’s Lullaby, a domestic riff on the Greek mythological creature Medusa, received a “Coup de Coeur” mention as one of 36 shorts in the catalogue selected by viewers as their favorites in the festival.

Chica — who was born in El Salvador and raised in Montreal, Canada — gravitates toward the supernatural in her filmmaking projects, yet always grounds her work in humanizing elements — the pain of loss in Serpent’s Lullaby, coping with illness in Ceramic Tango. Her most recent project keeps that theme alive, and in rather clever fashion. It’s an assault on our natural human sensitivities, tugging in several emotional directions all at once. The giddiness of a family of anthropomorphized pumpkins provides a comic backdrop to what can only be described as the rather grisly, systematic butchering of a human head for home decoration.

GALO caught up with Chica recently via phone to discuss this year’s Cannes entry, her filmmaking style, and how killer pumpkins can reveal a different side of our entrenched traditions.

Editorial note: Portions of this interview have been edited for length and clarity.

GALO: In A Tricky Treat, there’s a clear juxtaposition of horror and comedy — family members laughing and enjoying themselves while desecrating the remains of a man they captured as part of an annual tradition. How did you seek to strike a balance between levity and horror?

Patricia Chica: When we think about the horror genre, we think about gore, slashers, blood [and] fear. For me, it’s more about social commentary, psychological drama, the psychology of the character — and that could be really dark. So when I was given the opportunity to work with [executive producer] Tara Kurtz and [writer] Kamal John Iskander, we wanted to create something where the horror would support a social commentary. The only way to make it really impactful for the audience was to go to the extreme — to use the gore, the blood, the disgusting, the vicious type of imagery — so [that] at the end, people get it [and think]: ‘Oh my God, this is what we do to animals sometimes. We do this to nature.’ This man [in the film] was decapitated and completely transformed and killed, mutilated. It makes us think better.

The comedy element was to make it light and acceptable for the audience, otherwise people would just turn off the TV, computer, or leave the theater because it’s too gory for the sake of being gory or violent. And that was not my intention. My intention was to keep it light — it’s comedy, it’s funny — but there’s a strong message at the end that makes us think. All my films are the same — it’s a way of showing the darker side of the human psychology.

GALO: It seems like you’re drawn to projects with some sort of supernatural element, ultimately rooted in that human experience you mentioned. This is the case with A Tricky Treat, Serpent’s Lullaby and Ceramic Tango, for example. What is it about this theme that intrigues you as a filmmaker?

PC: I believe if we don’t anchor stories in humanity, human experience or our own psychology, there’s no point. There’s no reason to spend so many months working on a film if I don’t bring something to the audience. I have to contribute to something that is more important than the project itself — to make people think, make people talk, open the discussion about the subject matter. Maybe we don’t like to talk about it, or maybe it’s too serious to talk about, but those films kind of open up the dialogue. That’s very important for me as a filmmaker — to have purpose, to tell stories that have a strong message. I gravitate around writers or materials that really make me become a better filmmaker, just because I am finding the light within the darkness.

GALO: Let’s go back to the horror and comedy aspect of the film. Most of the horror came via the visuals — a slow-motion zoom-in on a silhouetted figure in a dark garage, another man’s shadow on a rainy driveway, not to mention the decapitated head. And then most of the comedy comes from the sound — the playful music and the lighthearted banter of the family members.

PC: I knew the position of both visual and [musical] would work when blended together. If you turn off the sound of the movie, you might not want to watch it because it [is] too disgusting or too gory. If you just listen to the soundtrack, you won’t have a clue of what this family is doing. I knew the imagery had to be horror. That’s how I visualized it — I visualized it very visceral and very graphic. And the music choice, I thought about [it] a lot when I was in post-production. Should I put scary-movie suspense sounds [in it], and [make it] creepy, scary, and then I thought, ‘no — this has to be really pure comedy. It has to be the opposite of what we’re seeing to make it really impactful.’ I’m happy I made that decision. I wanted the film to be timeless, too. It’s not necessarily anchored in a year — it could be 2015 or any time from the past.

I received a two-page script and did a table read with the actors where I experimented a lot with them, and the first read was very dark. I told them just make it funny and make believe [the human head] is a real pumpkin, and they started becoming playful with their acting during the rehearsal. A lot of the lines in the film came from that rehearsal. There was a lot of improv involved and I kept a lot of that in the final product. That’s part of my process as well. I allow the actors to really explore outside of the box, going the opposite way. If it’s a dark film, let’s make it lighter. If it’s comedy, let’s get serious and see what comes of this process. Ideas blossom, and it’s always very enriching for everyone. It just makes the concept go a step further every time.

GALO: Many of your projects — A Tricky Treat, Serpent’s Lullaby, Ceramic Tango, for example — are shorts. What draws you to these types of films more so than feature-length projects?

PC: I earn a living working for TV, so I work on long formats like TV series and things like that, but I don’t really publicize too much about it because it’s not mine. I’m just hired as a producer, director, whatever. So why haven’t I made a feature? I’ve been offered feature films many times and the screenplays I’ve received aren’t very strong, or need a page-one rewrite, or the production company wants to cut corners and they don’t want to give me enough space to polish an idea, or want to impose a certain actor who I don’t think is the right person for the role. It’s challenging when you want to do quality work — to find the right partner, it takes time, and that’s why it’s taken me longer than other filmmakers. I know [that] when my first feature comes out, it will be a great project. It won’t be straight to DVD and you forget about it. I’d rather have a career with three outstanding movies that will be memorable in the audience’s mind for many, many years than just have 15 features no one knows about.

GALO: You mentioned how some of the scripts you receive aren’t great or need a little bit of work. Have you thought about writing a screenplay on your own?

PC: Absolutely — I’m not a great writer, to be honest with you. It’s not an enjoyable process for me to be a writer. However, I now have two writers I’m cooperating with. One is the one who wrote A Tricky Treat — he wrote two other screenplays for me, one we just finished a new draft of last night. How I function is I bring the concept, and then those writers know me so well [that] they will kind of connect with my ideas and be on the same wavelength. They write, and I give comments, rewrite a few things and make them my own. It’s a very strong collaboration. I’m a storyteller, I’m not a writer. When I work with those writers, I feel I’m on top of things because I don’t have to sit at a computer for two to three months — all my ideas are really injected; my DNA is on the page. All my films have been the same process. And when you read the screenplays I receive and the final product on screen, it’s very different. But the original concept is there.

GALO: I imagine that has a lot to do with your process, making it more organic through improvisation.

PC: Yes. On Serpent’s Lullaby, the concept became alive when we found the mansion where we shot, and other possibilities became real. Serpent’s Lullaby was a three to four page script that became a 12-minute film.

GALO: There’s a clear riff in A Tricky Treat on the Halloween tradition of carving a jack-o’-lantern, but the roles are reversed. What message did you want to impart to viewers?

PC: The message is just to make society realize how we exploit and harm nature and animals for the sake of ceremonial tradition. The waste — when we cut trees for Christmas, when we overproduce pumpkins for Halloween. I just wanted people to realize this is what’s going on. It’s a tradition, it’s a cool thing to do, but is it the right thing? It’s up to you to decide. I’m not saying it’s a bad thing, but sometimes there could be other ways. For example, all the pumpkins after Halloween, people throw them in the garbage, but there are ways to recycle the pumpkin by opening it up and putting peanut butter in it so the squirrels can eat it in the backyard. Instead of cutting so many trees for Christmas, why don’t we create a tree with recycled materials? It’s just to make you realize [that] if we did that to human beings, it would be wrong because we’re killing a man just to have a head as a decoration.

If you’d like to catch “A Tricky Treat” before it comes out on VOD, you can see it next at the Fantasia International Film Festival in Montreal, the Scream Queen Filmfest in Tokyo, and the RIP Horror International Film Fest in Hollywood. To learn more about the film as well as Patricia Chica’s latest endeavors, follow her on Twitter @PatriciaChica. || Featured image: Filmmaker Patricia Chica. Photo: Kraken.