Director Peter Mettler Explores the Past, Present and Future in His Documentary, ‘The End of Time’

“It is often necessary to go to extremes in order to discover something that jolts us out of our usual thought patterns and rhythms, or provides a new perspective on those thought patterns.”

Peter Mettler, filmmaker, photographer and live audio/visual mixing performer, has a knack for going out into the world and finding film-worthy subjects. His visionary talents were authenticated in his illustrious documentaries Gambling, Gods and LSD (2002) and Picture of Light (1994), and his independent creativity solidified his “non-identity” in terms of categorizing film. With his newest documentary and experimental film The End of Time — which opened November 27th through December 5th at the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York — it would seem that this time, he bit off more than he could chew. It’s easy to be overwhelmed and come off pretentious when delving into the philosophical inquiry of “what is time?” and trying to conceptualize it, and, at times, it does take a turn down that unwatchable road. Interviews and narrative voiceovers describing different definitions of time make the film almost seem full of itself, making Mettler look like an all-knowing higher being. Contrary to this first impression, however, the real world footage, 3D imaging, picturesque landscapes and psychedelic sequences of audiovisual stimulation show that, in fact, Mettler’s unprecedented film transcends any previous perceptions on the idea of time.

Time is an impossible subject and it is allusive in nature. But this Toronto-born, Canadian and Swiss native found a way to tackle the mind-bending topic from a scientific, poetic, natural and religious standpoint. Over a three year period and after traveling across continents, the viewer is immersed in a film that in itself is a time machine. It is a journey from the CERN Laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland, to see the inner workings of a particle accelerator, to the Big Island in Hawaii, where miles of oozing lava flows destroy all but a small community; from the funeral pyres in Bodhgaya, India and Buddha’s site of enlightenment, to a desolated Detroit to explore the techno music world. The carefully crafted film, a First Run Features release, is a continuous collage of natural and technological clips and soundtracks which challenge our minds to the point of being uncomfortable over a span of 114 minutes (which Mettler, in a past interview, agreed is “painfully slow” compared to the shorter 109-minute version due to differing frame rates), and makes the audience acutely aware of how strange the passing of time can be (in this case, that it’s going by slowly).

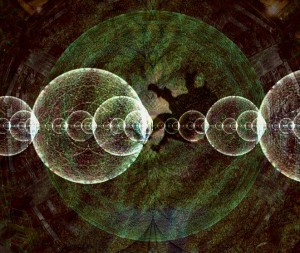

This sense of lagging ceases abruptly at the end of the film when the spectator is confronted with Mettler’s perplexing kaleidoscopic mesh of musical and visual dialogue. Creating a hallucinogenic-like experience, this type of unique “live cinema” may cause some to immediately reject the idea; however, after careful digestion and thought, one can readily appreciate the film for what it is — art. The gentle and mellow-toned director does not apologize for his distinct point of view, and he doesn’t need to. In the 2005 publication The VJ Book, author Paul Spinrad interviews Mettler about his fascination with this type of performance and his collaborations with various artists. His image and sound “mixology” is unparalleled, and clearly its ingenuity is recognized, winning him many prizes and national recognition.

Looking to give us a better understanding of the man behind the camera and the methods to his madness, Mettler spoke with GALO about cinema as a time machine, how piano lessons helped mold him into the live performance genius he is today, and his view of technology as a paradox in the modern world.

Editorial Note: Portions of the interview have been edited and shortened.

GALO: The film starts out with real footage of U.S. Air Force Pilot Joe Kittinger jumping out of a helium balloon in 1957. Why did you choose to start off with that particular moment in history, and how does it relate to the overall theme of time?

Peter Mettler: Perhaps, I should start by saying that the way that I work is very exploratory and often intuitive. I’ll start collecting things that seem to have some connection to the themes that I’m pursuing, but that aren’t obviously clear right from the start, and they find their place in the whole construction during the process or by the end of editing.

With that particular footage, I’d always wanted to start a film with someone who was falling to Earth [laughs], so that the Earth could be a kind of protagonist in its own right. The idea of seeing a human being in space and the Earth beyond is a very unusual perspective that most of us have never seen. I wanted to have a character just like that, but when I found that footage [of Kittinger], I was also amazed at the kind of primitive nature of that experiment —they go up in a helium balloon and had a 16 mm camera in the carriage that could be turned on before you jumped. The whole thing was kind of preposterous and was at the leading edge of science, and that really attracted me to it. It was only as I researched the footage more during editing that I heard stories from Kittinger about his experience of falling through the air and having the feeling that time had stopped. There was no wind, no resistance, he wasn’t sure if he was even moving anymore, and he really had this feeling like time had stopped. That kind of clinched it for me, to use those threads in the film. So it’s introduced with him, and later, in the montage toward the end [of the film], he’s reintroduced with the idea of time standing still.

GALO: Tackling a film based on the question “what is time?” seems daunting. How did you go about addressing this abstract idea and what made you think you would be able to successfully capture it through cinema and turn it into something tangible?

PM: As I said, in terms of the process, I kind of start with something and build from it, as opposed to writing a script up front. And to tell you the truth, I wasn’t beginning the process with the idea of making a film about time; I was actually starting with the subject matter of clouds, water and meteorology, and looking at what goes up into the atmosphere, how it travels around the globe, how the water comes back down onto Earth, how it enters our bodies, and all these different cycles of water. That’s where I began my research. In the process of that, I think I became more and more aware of transition, change, evolution, growth and entropy by looking at weather, in fact. As one of the physicists in the film said, “in many languages time and weather is actually the same word (in French, le temps),” and I think that’s what happened in my sort of course of inspection.

By looking at transition and weather, I start becoming more aware of time and what is time, what is our perception of time, and is it only a perception, in fact? Is it the way human beings organize their experience of being here? I head into the time tunnel, which is a very difficult subject, obviously [laughs], and I definitely wrestled with it because it’s kind of preposterous to make a film about time. You can’t say anything conclusive about it. The more research I did, the more it became apparent what a vast, omnipresent topic it is; everybody has something to say about it. There is no way it can be represented in a film. So [I included] all the different points of view — I ended up going about it very subjectively — by choosing the four or five places I thought would be good places to visit (with the idea of time). For example, the idea of geological time took me to Hawaii; the idea of the Big Bang, of the beginning of time, took me to the experiment in CERN; the idea of being in the present took me to Bodhgaya, which was the site where Buddha had his enlightenment, and so on. I organized it as a sort of exploration around locations that would offer a set of associations, ultimately, for the audience to muse on time.

And, of course, cinema in itself is the art of time, or one of the arts of time. Every film that’s made is also a film about time because you’re completely manipulating it the whole way through.

GALO: It’s no secret that you like to experiment with visual, light and sound mediums in your films — like in Picture of Light and Gambling, Gods and LSD. It is very present in The End of Time as well, creating mind-bending moments. How did you become interested in this unique and creative expression? Do you see it as a direction of cinema that needs to be explored more? And is it a way to set your documentaries apart from others?

PM: For me, it’s just something that evolved quite naturally. I think everybody has a kind of visual or musical sensibility that manifests [itself] into the work that they do, the art that they create. When I was very young, my parents made me study piano from 7 to 14-years-old, and I didn’t really like the discipline aspect of it, where you had to learn written pieces (which I did); but, what I did enjoy was [during] off hours being able to improvise on the piano and create musical journeys. An accompaniment to that, I was always in my mind visualizing things, imagining a kind of story or a scene, or something that had a drama built into it. Shortly after I started playing the piano, I got more and more into improvising and also had the opportunity to join a supreme film club in high school. As soon as I tried that, I felt an affinity between image and sound and knew that that’s what I wanted to do with my life. I also saw it as a medium with which you could explore the world.

You could really apply yourself to any subject or situation by making a film about it. The kind of musical nature of the work that I do came from way back then, and the exploratory nature of it also was a part of the way of life I felt was possible. I don’t really do it deliberately to set myself apart or to do something different, it’s just something that evolved that way. I think film forum can be very musical. You can create film like you create music out of a composition. You can have varying degrees of narrative, or story, dogma or essay; you can suggest things and let viewers find their own way to connect the dots, or you can be very explicit and write something out and tell the story. I tend to go toward the first one, where I set up a bunch of related ideas and let the viewer crystallize that.

(Interview continued on next page)