Director Peter Mettler Explores the Past, Present and Future in His Documentary, ‘The End of Time’

GALO: One quote from the film is from a man in Hawaii living in the last house in an area destroyed by lava from the Kilauea volcano, “It’s amazing how much you can do without. The trappings of the civilized world; it all costs something.” In our digital and technology-based age, do you think we are wasting time and it’s actually keeping us from being present and enjoying life?

PM: I think that’s also something I’m preoccupied with. Even the process of making or watching film is something that’s distracting us from being present in nature. We are really becoming addicted to our technology, and it’s affecting the way we see things and the way we behave. And Jack Thompson — the guy in the volcano — is someone who has quite removed himself from that. He does have a TV. When we were visiting him, he was watching TV, so he’s still connected to that stuff. It’s a paradox that we live in modern life — engaged in our technologies and being ruled by them. Time itself is a little like that — how we’ve developed clocks and meters to gauge our experience to create value, or to have an hourly wage to determine how much we’re worth — all that starts to become an imposition upon the way we live, which may be something that originally was a tool to help us, but, sometimes, you look around and they end up controlling us. I think technology can be like that in a lot of ways.

GALO: Speaking of technology, you use Mixxa in the film, which is a software demo that allows you to play with several film and sound clips at once. Was it a conscious decision to incorporate this abstract experience so as to challenge the viewers’ perception of time? Do you think these moments get your point across more effectively than the interviews and landscape sequences?

PM: Well, it’s something different, that’s for sure. The Mixxa software is something that I’ve been involved in and developing for the last eight years or so, as a tool to perform with image and sound live; and it all comes back to the musical sensibility of filmmaking and the improvisational aspects of filmmaking that I’m attracted to. First of all, that medium is something that I’ve been developing over the years. When it comes to exploring the themes of the film, and when you get to that passage within the film, to me it does represent another way of looking at both film and time — where things have become layered, compressed and refer back to things that we’ve already seen, as well as show new things that we haven’t [yet] seen. [These manipulations] are suggestive of the different languages of film, just as they can be suggestive of a different way of understanding time. It’s a provocation at that point in the film because, until then, it’s been a fairly digestible film, I guess [laughs] — to hear people talking and have landscapes, and then suddenly, you’re confronted with something that for some people is not so comfortable, while other people can readily get into it… It’s proven to be a part of the film that gets discussed a lot and that there is resistance toward, but I stand by it. I put it in there for a reason, and the reason still makes sense to me.

GALO: I think that for some people, it’s out there for them and not very common, but it makes it different.

PM: It’s amazing that the biggest reference I hear from general audiences is to [Stanley Kubrick’s] 2001: A Space Odyssey. The sequence in there is referenced a lot. For people who have come out of the art world or out of experimental film, [as well as] history from the 60s and 70s, that’s a language they’re familiar with already. It’s interesting as far as cinematic language goes because, not that long ago, when it [first] started, cinema was introduced by single shots, like the one of the train coming into the station. When they played that image in the theatre, the people in the theatre ran out of the way because they didn’t understand yet. Single shots began cinema. Over time, there’s a language that developed, which included close-ups, people, reverse shots in conversation, and a kind of language was developed out of that, which is still quite dominant in the way that we see films. Of course, film can be anything; it can be anything that’s in your imagination. It can be reminiscent of a hallucination or something completely abstract; it really knows no bounds because its bounds are the same as the human imagination. I really wanted to make that point — that a lot of how we understand the world is based upon concepts that we’ve agreed to socially, but there’s a lot behind those concepts.

GALO: One concern when it comes to any documentary is having an excess of material and not knowing what or what not to include. What was your strategy going into the editing process? And why did you decide to include in the film a glimpse into this process with a view of your editing suite and images from the film on a video monitor?

PM: I included that because, as I mentioned, any film is a film about time. I wanted, fairly early on in the film, to draw attention to the medium itself that you’re watching, so that you are reminded that there are an array of shots and experiences. And some of the ones you see in the editing room are present or recently past, and most of them are anticipations of something that you’re going to see in the future that was recorded and constructed for this cinematic experience. It’s just a gesture toward that.

I chose the locations for their specific relationships to time — at least in my mind — and would go to those places and really explore. I would meet people and discover things, like Jack Thompson. I didn’t know I would find him when I was there. There was a back and forth process of editing — shooting something, editing it, learning from that what was good to go shoot next, building upon the edit, and going back and forth between shooting and editing until the film was complete. The last thing that was actually filmed was the Indian sequence, because I felt that was something that was needed for the structure of the film. In fact, there was not that much extra shot [footage]. In all the places I visited, most of the scenes I shot are somehow represented in the film, which is quite different from the film I did before, Gambling, Gods and LSD, where I had mounds of material that I could never put in the film; and I was sad about that, so I didn’t want to repeat that.

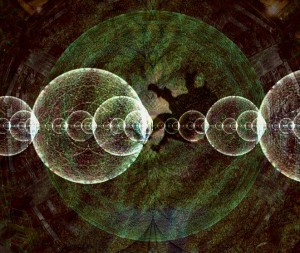

GALO: In The End of Time, there is a religious undertone. The array of circular shapes, like that of the enormous disks at the CERN Laboratory in Geneva, and the 3D geometric shapes, all resemble the Buddhist mandala symbol, which represents the universe. The relation between time and space is also a constant theme. Did you realize this connection beforehand or did it develop while filming?

PM: Those were a relationship that developed during filming. I was immediately struck when at CERN, at the disks and how beautiful they were — they did remind me of mandalas already then. What I didn’t understand so much is why they were shaped like that. When you think about the Big Bang and the expansion of the universe, you can visualize it as an orb that is getting bigger and bigger and blowing out in all directions. In fact, that’s how those disks at CERN are set up — to detect the expanding particles after a collision. Then I thought that maybe the Buddhists figured that out in their own way, in making the mandalas, because it’s actually something that seems to be a part of nature. You can think about it in other respects as well; like if you were to walk into the water, the rings that go out in all directions of the surface; and your own actions, in how you create rippling effects for all the moves you make. That visual theme was something that came out of watching and thinking about nature. The [shape] that you described with the software was actually made by two musicians, Bruno Degazio and Christos Hatzis, and is a visualization of harmonics with music. You’re actually seeing 64 harmonic notes merging together with different degrees of intensity and creating the line patterns in that circular system. It’s very mathematical, and it’s a tribute to things that Plato and Pythagoras were pursuing when they were interested in the idea of the music of the spheres and the music of the universe.

GALO: As someone who was born in Toronto, and is both a citizen of Canada and Switzerland, you are influenced by differing culture and lifestyles. Was it important to you to include people’s viewpoints that are from different cultures, especially given that time is a universal concept? What would draw you to film certain people, such as the tribal dancers in Hawaii or the girl from Detroit who’s part of a new community project?

PM: Representing different cultures or points of view as a subject is something that is important to me, and has grown in my experience over the years by traveling and going back and forth between Europe and Canada. Working between those two worlds, and using that juxtaposition in a lot of respects, has allowed me to create my work. It just evolved that way. My parents came here and I was born here, and I went back to their home to see what it was like, and one thing led to another. There’s no common thing to every person, but, ultimately, it was to find a thread that related to the body of the film, so different people would spark different attractions.

For example, I went to Detroit because of the idea of “era.” You had this city which was in its glory days of the automotive industry – it was at its peak — and then started crumbling and falling apart and becoming abandoned. We all know that if you look at Detroit, you see a degree of abandonment and nature taking over again. But in the midst of that, you have people bringing new life, with a whole other point of view and value system – they’re buying up blocks of houses, planting gardens, and working together in a way which is quite different from societal models of mainstream America. To me that was a kind of new era of possibility. And techno was also born in Detroit, in those ruins, and is emblematic of the digital age that we’re in; techno music to me has great kinship to the idea of digital art and information. That’s just one example of how something would attract me. I tend to find a spark and then connect it associatively to other aspects of the film.

GALO: Recently, you’ve been developing image performance software tools with Derivative Inc. Can you talk about this and your fascination with live video and audio mixing? How do you plan on continuing to experiment with this medium creatively?

PM: That’s the same software as Mixxa. That section of the film that’s layered is actually a performed thing. It’s a world of working with images and sounds that’s more improvisational than the editing stage, and that can take you to places that are unexpected. Sometimes it just falls flat on its face, but sometimes, you come up with really remarkable combinations and juxtapositions, and you get to places you wouldn’t necessarily get to if you were thinking about constructing it, moving slowly, and editing in that traditional way. I’m quite excited about pursuing that and bringing in aspects of more classical filmmaking into the improvisation with those performances, and vice versa.

“The End of Time” is currently playing in theatres. For more information, please visit www.firstrunfeatures.com.

Video Courtesy of: First Run Features.