From the Ballet Russe to Outer Space Melodies: A Q&A with David Raiklen, a Composer for the Ages

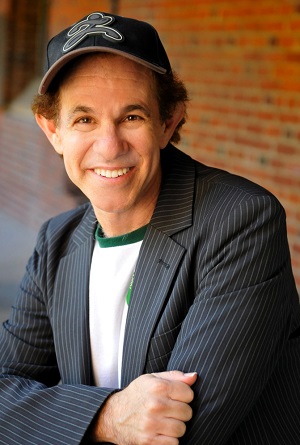

Film composer David Raiklen. Photo Credit: David Raiklen.

Where there is music in whatever form it takes — live concert, film, TV, ballet, even radio — there you will find composer David Raiklen. Most recently, his musical muse is Mia Slavenska, the once glittering leading ballerina of the famous Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the star of Mia, A Dancer’s Journey (an acclaimed new documentary that explores the life and art of this phenomenal performer). Featuring the narrative talents of actress Blythe Danner, the film traces Mia’s early beginnings (born Mia Čorak on February 20, 1916) as a child star in her native Croatia, her rise as the prima ballerina of the Zagreb Opera at 17, her flight with the Ballet Russe to the U.S., and the legacy she left in the universe of dance around the world.

On February 6th, I had the pleasure of interviewing Raiklen by phone upon his safe return to the West Coast. As we swapped stories about snow flurries and plane delays, I all the while found him in good humor. For such an auspicious and well-respected composer, he’s a very affable, down-to-earth guy. It was easy to get right to the heart of his exciting array of ongoing projects.

GALO: Let’s get right to Mia, the current documentary you’ve played such a key role in — I’d really like to get a sense of the genesis of the project: what drove you to it, what got you interested. Did the director Kate Johnson approach you, or did you find out about it in some other way?

David Raiklen: The process began back in 2005 when Maria Ramas, Mia’s daughter [who co-directed the film with Johnson as well as served as the producer and writer], went to Croatia and the government helped provide a camera crew and support for the filming of the state funeral for Mia; that’s really when the project began in earnest.

GALO: Had you met Maria before that time?

DR: No, I hadn’t. So that’s how the project really got started. The amazing revelation is that instead of being forgotten after the government banned her, it was the [country’s] love that gave her mother the funeral and got everybody’s interest up in learning more about her story. Kate Johnson came into it because she’s known in the dance community as a great director. She makes wonderful films — she’s especially sensitive in terms of making dance come alive on film. They made a short film, which ended up being submitted for a grant — the Roy Dean grant, administered by From the Heart Productions. They’re wonderful at getting documentary filmmakers’ projects finished.

GALO: They’ve been established for several years, I take it.

DR: Yes, I’d say like 20 years. [After a little bit of research, we found that they have been around for over 23 years — looks like Raiklen was right on the mark!] You can see from their site how many films they’ve helped get completed with every kind of assistance, from finding talent, to distribution, to fundraising…

GALO: That’s wonderful to know.

DR: And they [the Mia crew] won… I score films for them that need to have music. Some projects come in with no score or with temporary music from different places, and this was a project that needed some good music from beginning to end.

GALO: Of course.

DR: So I started working on it, and I’ve been there for about six years.

GALO: On this one project.

DR: With other projects in-between, of course.

GALO: That’s the way it goes sometimes before everybody’s aboard — even with the best intentions. I know what that process can be like, sometimes just getting a short play up can be quite an undertaking. So this was obviously an inspiring project with Mia’s involvement as a dancer, her involvement with the Ballet Russe. I think you had worked on a Russian ballet project before?

DR: Yes. That was the Russian Ballet on Ice…an ice dancing championship. They came and toured around the U.S. and the world, and I helped provide music for them to skate to. The Russian approach to ice skating is to bring in a lot of dance elements, especially ballet training. That was a great project; it was one show that had a specific sound with some variety, while the Mia project covered the whole 20th century.

GALO: That’s a pretty comprehensive life to have to write the music for. Tell me if I’m right or wrong here — the combination of works that you’ve created for this film was based around a recipe of adapting certain classical dances and adding original music to fill in around her life.

DR: That’s a pretty good description of what we did. Because the subject, Mia Slavenska, was a star dancer in the classical world, we had archival footage to show what an amazing, remarkable artist she was. So, we could use the music she actually danced to. It was very authentic that way. It’s a more dramatic and magical kind of story because not only was her life on stage something very dramatic and amazing, but her life off stage was also very dramatic and amazing.

[Laughter] Turning from being a child in a small town that had no dance school to becoming head of that national theatre by the time she was 18, and then being banned for life…then going on to become a movie star in Paris and New York, it was quite an amazing life, [and] that was part of the aesthetic of the film — traveling all over the world to have her life flow naturally with the music of the dance.

GALO: Were you very involved with the pre-production — the collaboration with the writer of the script or the director Kate Johnson?

DR: I was involved with the story’s development, and in a documentary a story is usually developed through the editing process. You have to make the story out of what you have, and often, you don’t know what you’re going to have until you’re well into the process…because we’re trying to get the archival footage in different countries around the world and we don’t’ know who’s going to say what, so until we have everything…

GALO: It’s a real potpourri. You almost have to get it all together and then figure out how you’re going to edit or assemble it.

DR: Right, right. And that’s why it takes so long to do a documentary. It’s not like you have a script that everybody agrees [on and says], “Yes, let’s go out and do it.” You have all these elements and when you have something new, you have to figure out how you’re going to fit that in.

GALO: I understand. How did Blythe Danner (Meet the Parents, Will & Grace) figure into all of this?

DR: Blythe was amazing. When I saw the film for the very first time, I was amazed by the artistry of Kate Johnson. She made these images dance in the most graceful and natural way. I’ve never seen anything like it. I was very impressed and I knew I had to do my best. I really enjoyed the narration, which I thought was being done by Mia herself. It turned out that was actually Blythe Danner, she so perfectly captured the voice and accent that she kind of transformed herself from being an acting star to a dancing star — very impressive.

GALO: Isn’t that fascinating. The first time I ever saw her was in an early TV production on PBS of The Seagull by Chekhov. It was just amazing. She did that with Frank Langella, and it was one of the most wonderful things I’d ever seen. It must have been sometime in the early ’70s.

DR: I wish I could have seen it.

GALO: Yes, well it’s probably still there in The Museum of TV Arts and Sciences (we checked, and it just so happens that the film is available on Amazon for rent and purchase) — it really was a transcendent performance, I must say. And then the play was on Broadway not too long ago with Carey Mulligan in the role of Nina. But I still remember the PBS version.

I’d like to bring up something of the genesis of your career as a composer. When you read these short bios of Mia, you see what an extraordinary dancer she was from the early age of six, hence it was amazing to find out that you were starting on keyboard at four or five. And then you composed your first film score at age nine. You must have had a lot of parental support for such a project.

DR: Well, this was the age when people had cameras that were commonly available, so you could tell a story. So, it was me and my friends and some help from parents… It wasn’t until we got older and more ambitious that we did a car crash with someone who could actually drive a car! We learned a lot about the art of cinematography and storytelling in film, because you can create an illusion (it’s very persuasive) by how you place the camera and how you edit in-between.

GALO: That’s true. So you were always enamored with film.

DR: Oh yes, I love film.