‘Herman’s House’ Is an Unsettled Case Against Solitary Confinement

In the opening days of 1967, Herman Wallace robbed a bank. A few days later, he found himself locked away in Louisiana State Penitentiary — known informally, and for many years infamously, as Angola. In 1972, he was convicted of murdering a security guard, his sentence was ratcheted up to life, and he was crammed into solitary confinement — a 6 by 9 foot cell where, aside for an abrupt stint in the general population, he has spent 23 hours a day for the past 40 years. No one currently incarcerated in the United States has spent more time in solitary confinement than Wallace. Despite the severity of his punishment, Wallace’s murder case remains a subject of much speculation and suspicion, and his troubled existence at Angola is now the subject of a film that seeks to expose the inhumanity of solitary confinement.

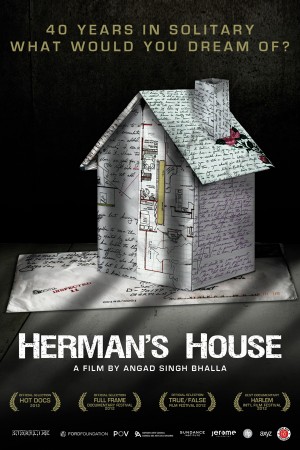

Angad Singh Bhalla’s new documentary, Herman’s House, examines the oppressive conditions of solitary confinement, the details of Wallace’s life, and the unlikely relationship between him and an artist named Jackie Sumell. After learning of Wallace’s lengthy confinement, Sumell decided to contact him in 2003. They’ve maintained a steady relationship ever since, and some of their early correspondence playfully revolved around the imagined characteristics of Wallace’s ideal house — complete with intricate blueprints, potential landscaping and furniture. Although Wallace and Sumell originally considered this little more than a “game,” the conversations and letters about Herman’s house eventually became the foundation of Sumell’s internationally acclaimed exhibit, The House That Herman Built. The exhibit has been featured in 12 galleries in five countries. Sumell now wants to build the house in New Orleans which, at Wallace’s request, would be a youth center for threatened children. The film chronicles this effort along with Wallace’s struggle for freedom and his evolving relationship with Sumell.

Although Wallace’s plight is often moving and always disturbing, a cogent case against solitary confinement never emerges from the film. Nor does a convincing argument for Wallace’s innocence — something Sumell seems utterly convinced of, but unable or unwilling to discuss in any detail. Without these much-needed components, the film feels like a missed opportunity — content to decry the practice of solitary confinement without contributing anything new to the conversation or providing the necessary context for Wallace’s situation.

Granted, Bhalla and Sumell are more interested in making an impression than making a case. The pure emotional spirit of the film is expressed by Sumell early on, “I’m not a lawyer and I’m not rich and I’m not powerful, but I’m an artist. And I knew that the only way that I could get him out of prison was to get him to dream.” In the film’s 81 minutes, the convoluted and ultimately unresolved circumstances surrounding the murder of a guard named Brent Miller (the crime for which Wallace was convicted and the sole reason for his confinement) are given scant attention. Wallace’s lawyer, Nick Trenticosta, merely says, “I was asked to represent Herman Wallace and I jumped at the chance because it was the right thing to do.” A statement like this loses much of its force when it doesn’t come with a single explanation.

In an interview with Malik Rahim, the man who introduced Wallace to the Black Panthers while they were imprisoned together, one of the most pervasive and problematic elements of the film is on display — the notion that Wallace is a great man who’s been horrendously and inexcusably wronged, full stop. Rahim also seems convinced that there will be widespread, vicious opposition to Sumell’s project and his comments on the matter are as crude as they are imprecise.

“When it comes to Jackie’s project, The House That Herman Built, they’re going to throw every obstacle at their disposal in front of her. You know, ‘we’re gonna make you work to do this. You ain’t gonna do nothing to honor this nigger that we hate.’” Rahim goes on to explain why, in his mind, Wallace is a heroic figure: “His spirit is a threat. You know, his whole existence is a threat to those who are really standing against peace and justice — because Herman is the essence of it.” Who are these bigots — these enemies of peace and justice — that Rahim is so confidently attacking? A deep sense of paranoia is ingrained in Rahim’s presumptions, which are extremely uncritical of one party and haphazardly damning of another. To Sumell and Rahim, Wallace’s innocence is never in question.

The film tells us, “Herman is appealing his murder conviction in the Louisiana state courts,” but it doesn’t offer any reasons why he should win. In one of the more bizarre sequences, Sumell argues about America’s penal system with an old man on his front lawn. When he says, in reference to solitary confinement, “You had to do something to get there,” Sumell parries, “They were Black Panthers who organized…do you think they’re applied fairly — the laws? They’re not, and that’s what the Black Panthers stood up against.” Contained in Sumell’s argument is the assumption that Wallace was convicted of murdering the guard solely because he was a member of the Black Panthers. While this claim is certainly plausible, given the atmosphere of animosity and tension at Angola in 1972, the onus is on Sumell to provide evidence for it. The possible political component of Wallace’s conviction is a fascinating avenue that could have been explored by the film, but it was unfortunately neglected.

Still, there are a few poignant moments in Herman’s House. When Wallace entreats Sumell to “Get my party ready girl,” a twinge of sympathy will find its way into all but the most hardened, unforgiving viewers. Throughout the film, Wallace’s dogged resilience and humor are genuinely remarkable. Listening to him joke with Sumell and make vacation plans with Robert King is grimly amusing, and you’ll occasionally find yourself hoping he’s acquitted. Herman’s House is commendable for bringing a marginalized voice out of the bowels of Angola and proving his humanity, if not his innocence. But this is the most worrying aspect of the film — it appeals to your irrational, volatile emotions over your mind. Near the end of Herman’s House, Sumell says of the “Angola Three” — the three Black Panthers originally sent to solitary confinement for the death of Brent Miller: Robert King, Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace — “Jesus, you know, these are heroes. These are gurus. These are amazing fucking human beings that I have a lot to learn from.” This wide-eyed reverence is charming, but it feels premature. And this is why the film fails — perhaps these men are far greater than this reviewer knows, but I’m just not convinced.

Rating: 2 out of 4 stars

Featured image: “Herman’s House,” a film by Angad Bhalla. Photo Courtesy of: First Run Features.