Making a Difference through Love and Medicine: Filmmaker Steve Hoover Discusses His Film ‘Blood Brother’

GALO: There’s a point in the film where Rocky is bringing pizza to the kids in the hospital. On the way there, beggars ask for some of the food. One of Rocky’s friends expresses concern that it feels wrong to indulge these kids while there is so much suffering going on around them. Do you ever have ethical concerns about the allocation of his time or energy?

SH: I suppose everyone should have ethical concerns about how we allocate time and energy. I included that scene in the film because I think it presents some logical questions people, including our crew, have about an American trying to do good in poor areas around the world. Rocky has said many times that he doesn’t want to recreate America for himself or bring it to the kids. He goes out of his way to avoid comfort and lives like the rest of the village. At the same time, it’s amazing how much American culture has spread around the world. I guess a lot of that is up to the audience… Rocky wants to give the kids a treat, they love pizza, and he buys them pizza. It’s hot, he’s tired, and he’s doing the best he can. My goal is never to present Rocky as a saint, but as a flawed person figuring things out on the fly, making mistakes, loving the kids.

GALO: The desire for an “authentic” life is relatively common among young people today. Do you think Rocky has found authenticity in India? If so, was it necessary for him to leave or could he have found meaning at home?

SH: I think Rocky found more than what he was looking for in India. Authenticity or the idea of living an authentic life is subjective. I think love, commitment and helping others are authentic things. I believe Rocky’s love for the kids may have been emotional at first but became authentic over time. He’s had many opportunities to leave, but he chooses to stay, for them. I do believe he benefits from staying, he has [formed a] family with them, but I think his life would be easier if he left. It’s definitely possible that Rocky could have found something meaningful here, but he didn’t. He did look in many different places.

GALO: In the film there are moments of tension between Rocky and the locals. Did you experience this when you went there?

SH: I felt tension the night that Vemithi died. The village was split on the decision to send her to the hospital, but ultimately decided that it would be best [to do so]. Unfortunately, that decision came too late. Of course, the blame fell on the one that initially proposed the idea. The important thing is that Vemithi’s family did not blame Rocky for her death. There was never a point when I was afraid, but there was tension at times.

GALO: Do you think the locals are uncomfortable around a white man from a wealthy nation living with them? While Rocky is clearly a laudatory figure, there is something uncomfortable about the idea of a white savior coming into a poor country to help the disenfranchised people of color.

SH: The villagers are probably more comfortable with Rocky than most Americans are with Indian nationals that come to live here. I wasn’t there when Rocky first moved to the village, but I do believe they were initially uncomfortable. For most of them, it would have been the first time they had ever seen a Caucasian man, so the discomfort would have been natural.

When I arrived, Rocky had been living amongst the villagers for a while. Many of them live more comfortably than he does. The village was very friendly toward Rocky and there were a lot of comfortable interactions between him and them. It was clear they had good relationships. We were invited to eat in many villagers’ homes, and he teaches in their school. I believe they got used to having a white man live among them. Unfortunately, people were a little uncomfortable with my wife though, who is African American.

Many Westerners are uncomfortable with white people helping in developing countries, and, often times, for good reason. Rocky doesn’t make sweeping generalizations that all the poor in India need his help or ours. He’s never charged anyone to join in his effort or anything like that. He did recognize a specific need that a particular group of HIV positive kids had that wasn’t being met and he felt he could meet it, which in a lot of ways, he was the one being saved. Rocky has met many educated Indians who learn of his work and express extreme gratitude for caring about children in their country. Especially given India’s history, it can be hard for them to believe that someone would do such a thing. People are often shocked and honored when he speaks their native, classical language. I don’t think it matters so much where you’re coming from to help or love someone, as long as you’re true. I have heard some argue that the kids don’t need Rocky, they need better medicine. I think that’s a shallow perspective. I believe they need both love and medicine. They are getting that and thriving.

Video Courtesy of: Blood Brother.

GALO: Are you still in touch with Rocky? Are there any new developments in his life?

SH: Overall, Rocky is doing very well, he and I talk often. We are in the process of building halfway homes for the kids that age out of the orphanage. Our goal is to supply vocational training to build a bridge to healthy adulthood. This is necessary because the introduction of HIV/AIDS treatment is allowing the kids to live longer lives. He’s in the process of starting a photography business that the kids will own and operate. He has been teaching some of the older kids photography for a few years now. Thanks to the film and new interest, there are many exciting developments.

GALO: How have you been able to support yourself while also making films? Did you ever have a day job? Do you have one now?

SH: I work for Animal, a production company in Pittsburgh. They produced and financed Blood Brother. I’ve been on staff with Animal for several years now.

GALO: This film has been getting great buzz. It must have been thrilling to win the Documentary Award at Sundance. I’m sure you’re getting hounded about what you’ve got in the works. Could you speak about any upcoming projects?

SH: Currently, I am in post-production for another character driven documentary about a Ukrainian man named Gennadiy. He’s a complicated man to summarize.

GALO: Most artists have role models that inspired them to go into the industry. Which filmmakers do you look up to?

SH: I often look up to my filmmaker friends and peers because I can see their struggles and relate to them. I respect them for fighting for their art, to share something. I have co-workers and artist friends that I deeply admire and aspire to be like. I feed off of their passion, and they inspire me to keep going.

GALO: There are many young people trying to be filmmakers today. What advice would you give to them?

SH: I really don’t think I’m the best person to offer advice. I’m definitely still trying to figure things out myself. I seek advice from my filmmaker friends. I try to get critical eyes on the progress of my projects and I take negative criticism very seriously, as painful as it can be. One thing that Rocky shared with me about his work is that it’s impossible to please everyone. That’s common sense, but it carries a lot of weight in times of extreme self-doubt. There’s always someone there to remind you that you suck in some way, and I guess that’s OK, as long as you don’t give up.

Video Courtesy of: Blood Brother.

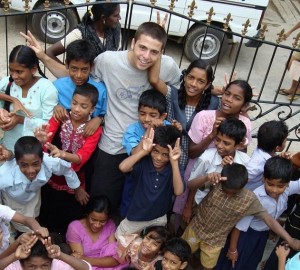

Featured image: A scene from “Blood Brother,” a feature documentary by Steve Hoover. Rocky Braat with the kids. Photo Credit: © 2012 Animal | A film by Steve Hoover.