Tribeca Reviews: ‘The Song of Lahore’ — How to Bring Down the House

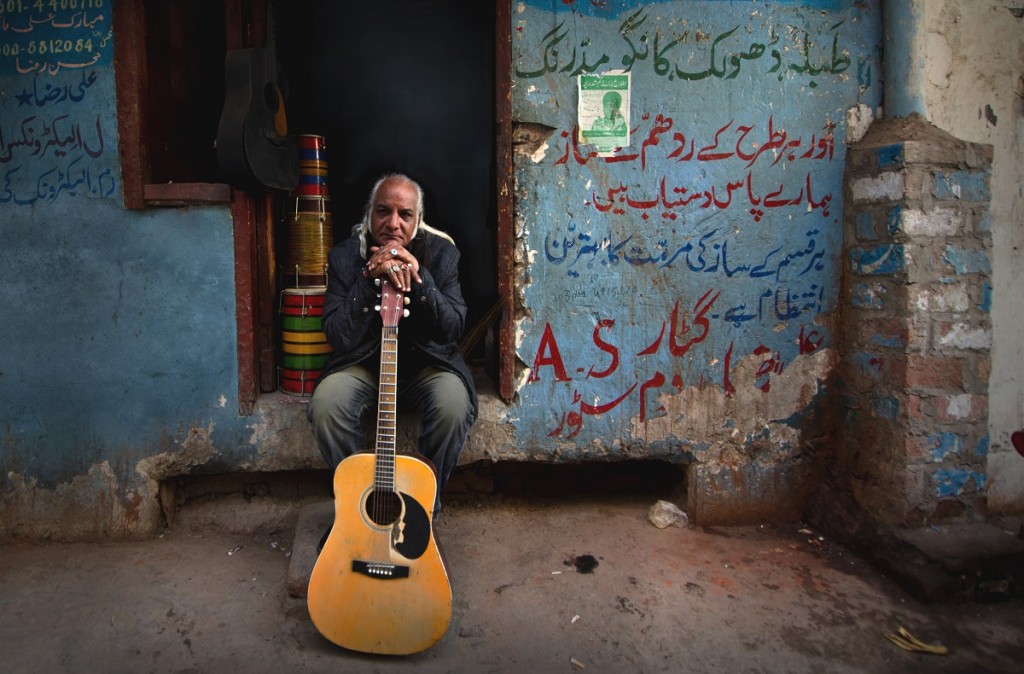

Pictured: Musician Asad Ali in “Song of Lahore.” Photo Credit: Mobeen Ansari.

In the 1970s, as disco and punk rock took root on American soil, a heralded music tradition dating back centuries was silenced in Lahore, Pakistan when radical Islamists took control of the country. By “applying the squeeze,” they instituted Sharia Law and banned music and dancing from a culture that had played center stage in the region for over 1,000 years. But the spirit and soul of a culture never truly die — particularly when people are willing to risk everything to keep their tradition alive.

The steadfast protection and continuation of Lahore’s music is at the heart of Song of Lahore, a new documentary by the Academy and Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy (Pakistan’s Taliban Generation, Saving Face, and The New Apartheid) and cinematographer-turned-filmmaker Andy Schocken (Beyond the Brick: A Lego Brickumentary). The film had its world premiere at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival and was runner-up for the Audience Choice Award for Best Documentary. It is a brilliant testament to the tenacity of a people living under oppression and driven by inspiration and soul.

Beginning with old film footage of visits by the Queen of England to faded clips of musical performances on set at Bari Film Studios (also banned), Chinoy and Schocken follow the lives of Lahore musicians, many of whom trace their vocation back seven generations. “Now there’s nothing left. Only crows,” opines Asad Ali, 63, a former guitarist at Bari Film Studios, as the film opens.

Cinematographer Asad Faruqi has an animated eye for street life in Lahore: the hustle and bustle of the cityscape comes alive as we see rickshaws weaving in and out of narrow streets, bored children atop buildings, and men congregating at their local coffee shop. It’s not just to create the mise-en-scène, however. As we learn, many of the city’s musicians lost their jobs in the 1970s and are now driving rickshaws or working in coffee shops. There are many scenes like this in the film — where what we are seeing today is actually the unraveling of a lost culture from yesteryear.

But there are those who could never be silenced.

Those who continue the tradition often do so in soundproofed apartments with thick shades and curtains drawn. “There needs to be pain in your soul to play an instrument,” one of them explains with a heavy heart behind closed doors. There is a sense of honor and embarrassment among the younger generation learning to play instruments from their elders — a juxtaposition that Chinoy and Schocken excel at portraying without mawkishness: honor, at being chosen to carry on the tradition; embarrassment that someone might find out and mock them.

Izzat Majeed, a well-respected businessman and musical genius, sought to change this.

In the 2000s, with a less controlling government (although the Taliban continues to force its will on the people), Majeed staked his life and honor on bringing the music back. He created Sachal Studios, gathering drummers, flautists, violinists, and sitar players to record the music of Lahore, but quickly learned that there was a definitive lack of interest among the youth who were drawn to Western-inspired synthesized music.

In embracing this intergenerational divide, Majeed encouraged his newly formed orchestra to experiment in the studio. And we have front row seats as they attempt new sounds — some better than others. When the mismatched group of players begins riffing on a variety of American jazz hits, they land squarely upon Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five.” Jazz improvisation, Majeed explains, is quite similar to that of Lahore’s musical heritage.

Their interpretation is an inspiring beat where East meets West with the whimsicality of a bird in flight — a rendition that even Brubeck noted was one of the best he’d ever heard. After the BBC does a special segment on their “Take Five” YouTube video, it doesn’t take long for composer and trumpeter Wynton Marsalis to invite them to play with New York’s premier jazz ensemble at Lincoln Center.

“Jazz is a music that comes from people who were always persecuted,” Marsalis declares, as he prepares for the arrival of the Sachal Studios musicians. East meets West again (a running theme portrayed with candor and jocularity by the directors), this time in the streets of New York City. We watch on the edge of our seats as the Lahore musicians enter the world of the Big Apple, almost tiptoe through Times Square in unabashed awe, and struggle to meld their music with that of Marsalis’ world-class ensemble.

What transpires is the gold of cinema. The filmmakers have accomplished what few documentarians achieve: they offer us an earnest, tug-at-your heart story without schmaltzy naïveté. Their subjects are tried and seasoned musicians, and — despite their own emotional breakdowns — Chinoy and Schocken allow them the space to experience tears and grief without sentimentalizing their journeys.

The denouement arrives a day before their New York performance, when both Majeed and Marsalis struggle to hide their frustrations with the flailing joint practices. And it is here that we realize that East, West, brown, black, Muslim, Christian, we are all humans who share similar emotions, fears, and exultations. “When people are soulful and want to come together, they do,” Marsalis notes, as they search to replace a key member of the Sachal orchestra.

The Lahore musical tradition, which for decades refused to be silenced, explodes onto stage with a fervent, live performance at Lincoln Center. And the Sachal Studio Orchestra returns home to battle the demons of oppression once again. As the screen turned black, there was nothing but smiles on the faces of my fellow moviegoers. The world seemed whole. Lives resuscitated. Cultures entwined.

If only politicians and war generals could stop and hear the music.

Rating: A

Video courtesy of sachalmusicchannel.

Video courtesy of sachalmusicchannel.

“The Song of Lahore” had its World Premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 18. For more information about the film, you can visit the TFF’s official Web site by clicking here.