Hard Right Turn: The Musical Journey of Frank Turner

John Lydon, known formerly by his stage name as “Johnny Rotten” of the Sex Pistols and Public Image Ltd., once said about punk, “It was a time when people decided to do things for themselves. It was about individualism and concern for our surroundings and the future — good, worthy things done with a glorious sense of rebellion.” Taking such assertions into consideration, it can be presumed that passion, attitude, and honesty are what matters most to many musicians in this day and age, regardless of what instrument they may be holding at the time of their performance or the atmosphere they have set out to evoke for the night; in the end, it all comes down to the message behind the music and the movement of continually changing the unwritten rules of its artistry. Whether it was the synthesizers that Lydon used with PiL after leaving seminal punk outfit the Sex Pistols, or musician Frank Turner, formerly of Million Dead, having a six string banjo in his repertoire, the only rules an artist follows are the ones they create or accept for themselves.

Turner had been immersed in music from an early age, almost since birth. A product of both nature and the nurturing of his parents, to the 30-year-old singer-songwriter from England, music wasn’t a lifestyle, but life itself. Turner knew almost instantly that music was what he wanted to do and it was the vehicle in which he hoped to travel and express himself.

“My parents are musical but not in a modern or pop music kind of way. I got into metal via Iron Maiden, and then through grunge into punk and hardcore. In more recent years, I got into folk and country music and have moved in that direction. I guess I always wanted to make a life in music ever since I fell in love with it,” Turner says.

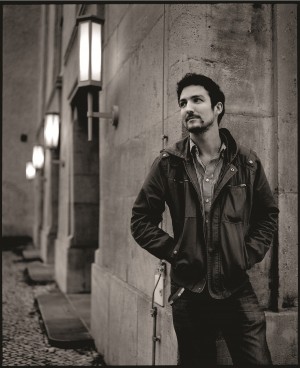

Originating during his school years, music quickly became a daily entity for the stylishly dressed, dark-haired, goatee sporting musician with smiling brown eyes, starting with the short lived band Kneejerk, which played numerous shows in the United Kingdom and had released three independent records before their demise. Shortly after disbanding in November 2001, Turner joined London hardcore band Million Dead after a fortunate phone call from his longtime friend and frequent band mate, drummer Ben Dawson, who had been playing on-and-off in bands with Turner since age 11. Their name found its origins through another hardcore band, Refused, from Sweden that Million Dead had admired and appreciated. Stemming from a lyric in their song, “The Apollo Programme Was A Hoax,” a track off Refused’s highly acclaimed album, The Shape of Punk to Come, singer Dennis Lyxzen shouts, “suck on my words for a while, choke in the truth of a million dead.” It was there, in the last line of the song that the name Million Dead was born.

“MD was a kind of an awkward hardcore band — we were into stuff like Hot Snakes, Jesus Lizard, Refused, and so on. I guess we had something of a thousand yard stare — we wanted to be intense and extreme, and, in later years, we got really heavily into later period Black Flag, both musically and philosophically,” Turner says.

The vast Atlantic proved a bit too much for Million Dead, as unfortunately, the band was never able to land a foothold in North America. Despite support, in both praise and radio play from renowned disc jockeys in Britain such as John Peel and Mike Davies, among others, (people who command respect in the American music press); Million Dead’s music wasn’t heard much outside the continent and British Isles. A band can play until their bones break and travel across the world with a wanderlust looking for success, yet good fortune and a sense of luck are also needed, and such an opportunity did not seem to present itself for the band.

True to the style and attitude of hardcore music, Million Dead was raw, fast, and abrasive, and visuals followed suit as well. Their first single, “Smiling at Strangers on Trains,” was released in late 2002 with a video featuring a homeless man urinating through a letterbox as well as on Cameron Dean, a band member. The video also contained brief images of sadomasochism, with a woman whipping a man in a leather mask, and possessing lyrics dealing with loneliness and isolation, “you were a single red blood cell, but I lost you in this knot of capillaries.” Million Dead was an outlet of frustration, hostility, and confusion of the outside world.

Yet, the fury the band expressed through its music toward their surroundings would find its way back to the band members themselves. As four years and two albums passed, Million Dead had decided to break up in 2005.

“Once the end of Million Dead rolled around, I just didn’t want to be in a band anymore. The last year of Million Dead was just murderous. Four people who want to kill each other, sat in a van driving around Europe; it’s no fun,” Turner had said in 2011 to Punk Ska Press. Turner has held his own to the same sentiments about the breakup to the present day, but nevertheless enjoyed the experience the band gave his life, “We broke up because we fell out with each other. It was pretty mundane, [but] much fun,” he says.

Much like Lydon, Lou Reed, and several artists before him, Turner knew he wanted to continue music, but to walk further down the same road when presented with an intriguing intersection seemed mundane to Turner, and so, he took a sharp turn into another genre: folk music, with a little twist by his crafty ability in keeping punk’s energy along with it. Turner’s new venture isn’t what one would think of when traditional folk is mentioned. A music lover wouldn’t want to approach Turner the way one would approach other folk artists such as Peter, Paul and Mary or John Denver. Even in comparison to Denver, a popular acoustic artist who blended country and folk similarly in texture to Turner, a wide fork separates the paths of the two. Turner’s shows are vibrant, dynamic, and leave a burning sensation similar to downing a shot of strong whiskey. The heat, the passion, and drive are felt at every square inch of a venue he performs. The live shows often swirl the energy from the performer to the crowd as lyrics and rhythms oscillate back and forth from the artist to the audience.

(Article continued on next page)