Benjamin Mack and the Box That Thunders

I awoke early, eyes resting easily on the smattering of other beds above and below me in what in previous times was obviously a storage garage (if the bay doors directly behind my bunk were any indication). Mbafana and I had agreed to convene in the lodge’s small parking lot at 9 a.m., leaving just enough time to try out the “banana shower.” While the cool water was refreshing amidst the muggy heat (it was the end of the wet season, after all), the lack of a towel — an oversight on my part — meant a naked man was running around for much longer than he would have preferred. Whoops.

Mbafana was just as cheery as he’d been the night before, hopping behind the wheel of the Datsun with all the earnestness of a diligent schoolboy on his way to class. The day would indeed prove educational, albeit in ways I could not have anticipated.

The roads in the city center were a bit better than near the airport, but it was still a bumpy ride as the two of us zigzagged and weaved our way through surprisingly thick traffic sans seatbelts. Crowds of people in shorts and other loose-fitting clothes, including men carrying bags and women balancing a menagerie of objects on their heads, thronged the sides of the roads. Considering how often they ran back and forth in front of moving vehicles, I deduced that jaywalking must not be a crime. The young men standing about selling newspapers in the middle of intersections were, I concluded, among the bravest human beings I’d ever seen.

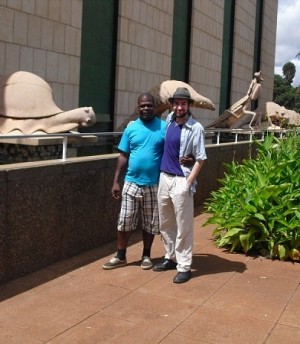

Zimbabwe once boasted the highest literacy rate in all of Africa, and consequently places of learning — from schools to museums — abound in Harare. Located in the southeastern part of the city, the Museum of Human Sciences looks rather like a university lecture hall from the outside, with a boxish brick design that immediately brought to mind my alma mater (Boise State University). Walking inside with Mbafana, we were greeted by a professorial-looking man with round spectacles at the front desk, and a smiling female security guard nearby. It was Sunday in this devoutly Christian country, but the museum was open nonetheless. The symbolism of glimpsing perhaps the most famous artifact in Abrahamic religion on the day traditionally known as the Sabbath was not lost on me.

“Good morning, how are you doing today, sir?” the man asked. That was one thing I noticed about Zimbabwe — every man was always referred to as “sir.” I wasn’t complaining.

“I’m doing well, thank you,” I answered. “How are you?”

We exchanged idle banter for the next few minutes, sharing views on everything from the weather, my impressions of Harare, to how busy the museum normally is. But the main question on my mind, of course, was the Ark.

“Yes, it is here,” the man said, his voice suddenly severe. It was as if the temperature of the room had suddenly chilled by several degrees. “Many come to see it; some for the wrong reasons.”

It was among the most ominous things I’d ever heard.

While admission to the museum is only $3 for locals, foreigners must fork over $10 to enter. The society is almost exclusively cash-only, but it was a small price to pay to see — literally — a piece of Heaven. The caveat: explicitly no photos, period, as at least five signs all screamed with big red “x” symbols over cameras. My encounter with the Ark would have to be eyes-only.

My heart was pounding. “Good luck,” called the man at the desk as Mbafana and I stepped into the exhibit halls. Destiny was only a few meters away.

Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’ cinematic version of the quest for the Ark may have been fraught with peril, but fortunately no booby traps greeted us as we traversed the halls. Instead, we encountered exhibit after exhibit documenting the history of pre-colonial, colonial and modern Zimbabwe. It was all quite fascinating, but the air remained buzzing with the electricity of anticipation for what lay ahead. It was hard to focus on anything else.

Rounding a corner in the midst of an exhibit on the Lemba and their contributions to Zimbabwe before the arrival of the British, I suddenly ran nearly smack into a large display case. Backing up several paces, my mouth dropped open as I gazed upon a large stone box, beside which was a placard with the words “Ngoma Lungundu” in big bold letters. There it was: the Ark of the Covenant. Good God.

Roughly two feet long by a foot high, the dimensions were close to those of the original Ark as the Bible describes them. The simple stonework was heavily cracked and chipped, devoid of any exterior engravings other than a faint interwoven design near the top that called to mind a rope. The original Ark of the Covenant was said to be made of gold and inlaid with precious jewels; this vessel looked more like a broken pot. It was also not box-shaped at all, but curved like a drum. Though there were holes where poles could conceivably be inserted, none were to be found at the present time. The top was missing, allowing one to see inside the holy vessel. And inside was…nothing. No Ten Commandments, no Aaron’s rod, nothing. So which part was from the original Ark, as the Lemba believed?

Emotions swirled like a maelstrom within me. I’d come halfway around the world for…this? I didn’t know what to think.

Mbafana joined me a few seconds later.

“Was this what you were looking for?” he asked.

“It was,” I answered.

He paused for a moment. “It’s nice.”

“It is.”

“I think there are other things more interesting.”

“Like what?”

“People are more interesting. The past is…gone.”

I smiled. “True.”

We moved on to the rest of the museum. I reflected on his words. There were indeed a lot of more interesting things I’d learned about, Mbafana himself not least among them. Maybe I hadn’t really “found” the Ark. But I’d discovered something far more valuable: a friend — that and some really great weather.